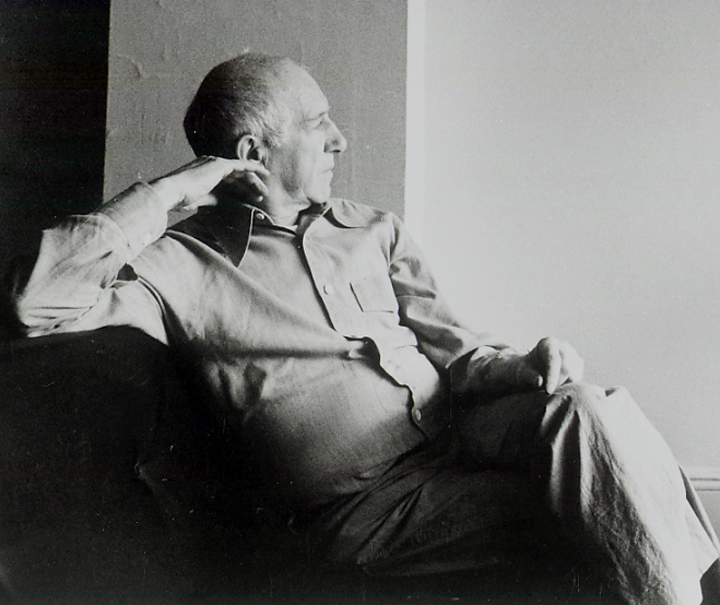

JT Interview: Jan 1971: An interview with Jack Tworkov, Part 2 of 2

An Interview with Jack Tworkov, Part 2 of 2

by Phyllis Tuchman / © Phyllis Tuchman

Artforum, January, 1971, pp 62-68

(The following interview was originally published in the January 1971 issue of Artforum. The interview appeared just months before Tworkov’s new paintings would open at the Whitney Museum of American Art and French & Co.)

Have you continued to make figure studies?

I draw from the figure more for the pleasure of just drawing. I don’t deny that there is for the artist a really great subjective pleasure in observation, in keen observation, and in seeing and setting down a three-dimensional object on a two-dimensional surface. But that’s a private pleasure. I don’t really see it as a factor in my painting. Whether it ever really could be, I really don’t know.

One critic recently wrote that he felt that in all the artists in the first generation there was one element in common: a syntactical conception (having to do with surface, paint quality, a way of acting before the canvas). Do you see this?

If you turn towards abstraction, you are always concerned with the means of the paint itself. Paint itself became important, became a subject for exploration. The way paint was put on became an important thing, as important for the painter as a gesture is for a dancer. Instead of reading meanings from references to nature, you had to read meanings directly from the artist’s gesture, from the sensibility with which he used paint or color (because that’s all there was to deal with). In other words, there was a reduction of the artist’s means to relatively few components and it was the way he handled those few components that made the expressive quality of his painting.

I think that technique is always important – even the rejection of technique is a technique. And there was a great deal of rejection of technique in Abstract Expressionist painting, which in itself became a technique of working. If Pollock dribbled paint, it was a rejection of one kind of technique, but it established another kind of technique. Certainly Pollock after awhile knew pretty much how he was going to make his picture just as much as any painter ever did. And all technique means is that I can repeat my performance.

Do you think that surface qualities or surface incident seen in the art of the first generation or Abstract Expressionism prevent a significant point of departure for artists today – or that activity on the surface is coming to be significant again?

That’s what I hear all the time, that younger painters are again involved with surface and with Abstract Expressionist painting. I haven’t seen enough of it; really, I don’t know. I think for me the important thing is that there was a naïve trust in random activity, in automatic painting, in the unconscious. I think it’s a little naïve to give it as much trust as we did. I think that it’s a very important aspect of an artists work to learn from the unexpected, to learn from accident. But I believe for myself in a kind of reconciliation between that and thoughtfulness. As I said before, I begin to see less and less conflict between intuition and reason. I think that both are integral processes, that the problem is to keep the painting open to both impulses. I think that if I have any conflict with the color field painters, it is their naïve exclusion of the hand, of the automatic and random activities in a canvas, their insistence on almost mechanical craft, comprising the conceptual, reasoning qualities to the exclusion of the other. I think that their extreme is naïve. Either extreme is only half of the story. I think that in painting, as in life, both play an enormous role. You wouldn’t be alive if you eliminated all impulse and you couldn’t live if you eliminated all thought. Generally, I think that this business of position holding is a bad thing in art. I’m sick of the whole thing of merely advancing towards a position and making a thing out of that position regardless of what kind of art results from it. I’m really more interested in art than in positions – regardless of styles.

Do you think there’s more a difference of space than of color paintings by first generation artists or Abstract Expressionists and color field painters of the sixties?

Yes, I think so. Of course, I don’t know what is meant by Abstract Expressionists, although I was considered an Abstract Expressionist. I saw no connection between my work, say, and Rothko’s or Newman’s. I admired Rothko’s work enormously, but I know that Rothko resented any identification with what was sometimes to be called action painting. The real difference there, really, was the emphasis of automatic and random activity, on the one hand, and the emphasis on deliberate design, on the other.

Rothko found a theme with which he stayed the rest of his life. Most of the people that I was associated with, in the fifties, thought of every painting as an exploration. We were not concerned with an identifying image. Every painting sought to push away from the periphery of previous experience. A lot of it failed, of course. As to where the question of space is concerned – Abstract Expressionist painters did not reject the idea of illusion, the illusion of depth. Certainly, I did not. I don’t know that there is more than a mere difference here, that there is a vital, esthetic principal involved. Except it seems that the whole century was moving constantly towards a further and further emptying out of the elements that make up a painting. And it was moving towards zero elements and actually we did get a kind of zero painting. And my instinct was not to go that far. The idea of negation has gone as far as I can bear. And if anything can be re-introduced into painting that had a yes quality rather than a no quality, I was for it. There was, of course, enough negation in my own work. But I tried to hold onto whatever I could. I mean that the constant moving towards zeromeans in painting was ultimately to lead towards the negation of painting; and I wasn’t ever prepared then, and I’m not prepared now, to say no to painting.

Were the paintings you did in the fifties directed by your gesture?

I think that there was so much talk at that time of getting away from French art. We wanted to get away from Picasso, we wanted to get away from Matisse. And the only way you could do it was by abandoning composition and to trust to intuitive, automatic action. And then the feedback from that kind of activity was a guiding point. The movement had very strong negative impulses: not to paint like Picasso, not to paint like Matisse, not to be influenced even by the painters one most admired. And this was so much in the air. Maybe the influence was Freudian psychology. The theory that automatic activity is psychology determined gave you a kind of reassurance, a trust in automatic activity.

Did first generation or Abstract Expressionist painting seem to relate to Cubism originally?

I don’t think we had too close a connection to cubism. My idea of abstract Expressionism was that it tried to skip the cubist period. Personally, I had a much stronger relationship to Cézanne and impressionism and the Fauves especially. They were much more meaningful to me than the Cubists. I think that today (maybe) ‘I have a greater appreciation of early Cubism, of Analytic Cubism. I really despise later Cubist work – whether its Picasso or anybody else’s. I never cared much for Braque as a painter, except his earliest Analytic Cubist paintings. I was always fascinated by Analytic Cubism, but I saw it as a spin-off from Cézanne and Impressionism. When I turned to abstract art, I wanted to skip the whole Cubist period. The Abstract Expressionists became much more interested in the psychology of automatic painting, of random activity in the painting, of undersigned, un-premeditated approaches to the canvas.

While I have an extraordinary fondness for Cézanne, I wouldn’t want to limit the answer to just Cézanne because I would rather say it’s what Impressionism as a whole meant. And that was an independence of the surface from the things represented. The surface of impressionism cannot be found in nature (at least it did not attempt to imitate nature), it can only be found in painting. But the surface of Impressionist painting, including the surfaces that Cézanne created, were invented forms through which nature was seen. It was like an invention of forms, a screen of forms through which nature could be looked at. But what the eye could actually see on the surface is not to be found in nature. There are no little color planes in nature, but they did exist in Cézanne. There are no dots; as there are in Seurat, but they became a form through which to build and through which to see. I think this is the terribly important and radical thing that Impressionism contributed to painting and that Cézanne was simply more lucid than most impressionists about this. There was a tremendous lucidity – and a kind of terrific passion, that people never mention, in Cézanne’s work. Cézanne’s lucidity came out of a terrific passion. There was a kind of order in Cézanne which was more or less conceptual. Fundamentally, just like the dots of Seurat had to be at random (he could not have planned every dot), only the total idea that he wanted to arrive at was conceptual. So, in a sense, Cézanne’s painting, with its recessions of planes, has to be fairly spontaneous and chancy all along. Only the overall concept was kept in focus. The actual doing was a step-by-step experience of the painting. And in that sense, you had to feel your way, which meant that you had to allow for random qualities. If at first Cézanne thought he could derive his painting from looking (like one always imagines Cézanne with a brush suspended in his hand, looking at the scene, and waiting for what the next touch aught to be), that might have been the way when he started out. But by the end of his life, Cézanne knew he could not make that painting just by looking at the subject. He really became abstract. If you took a look at some of his last paintings, the landscapes, it can no longer be related directly to seeing. He only had a general concept of the landscape. But the actual painting he really had to do from his head – it was no longer possible to see it in nature. So that Cézanne laid the basis for the abstract picture, as the Impressionists generally did.

I think, for instance, that abstract painting is inconceivable without the Impressionists. Abstract art could never have developed without Impressionism as a precedent. I think that as a precedent for abstract painting, Impressionism is perhaps more significant than Cubism, aside from the fact that Cubism itself derived out of Impressionism.

Why did The Club seem to slowly dissolve itself?

I think primarily because it became a career vehicle for some artists. And so then it lost its early innocence, you might say. There was an early kind of camaraderie that was kind of just for itself. It created a cohesiveness, you know. There was some cohesiveness among the artists that created The Club. And that was, just for a moment, a very nice period. The members, as everybody knows, came to be known as Abstract Expressionists, but no artist thought of himself as an Abstract Expressionist at the time. No one thought in those terms. No one thought he was going to have a great career; no on thought in terms of success. So The Club was just a place to talk, to drink, to dance, mostly to dance. It was a tremendous dance place. It’s the dancing that I look back to with nostalgia. Then they started these evenings, these discussion evenings which attracted a lot of people. And then more and more people saw The Club as a kind of “in” place. So it persisted for a long time. But a lot of people who were originally in it sort of dropped out, lost interest in it. I think that The Club was one of the few instances in my life where I remember the artists looking for something simple, something enjoyable, not opportunistic. For a little while, it was nice to be surrounded by friends. People were very close to each other. I imagine young artists have it today in SoHo. But the artists of my generation – what is left of it – don’t. They fell apart.