Jennifer Bartlett on Jack Tworkov (1987)

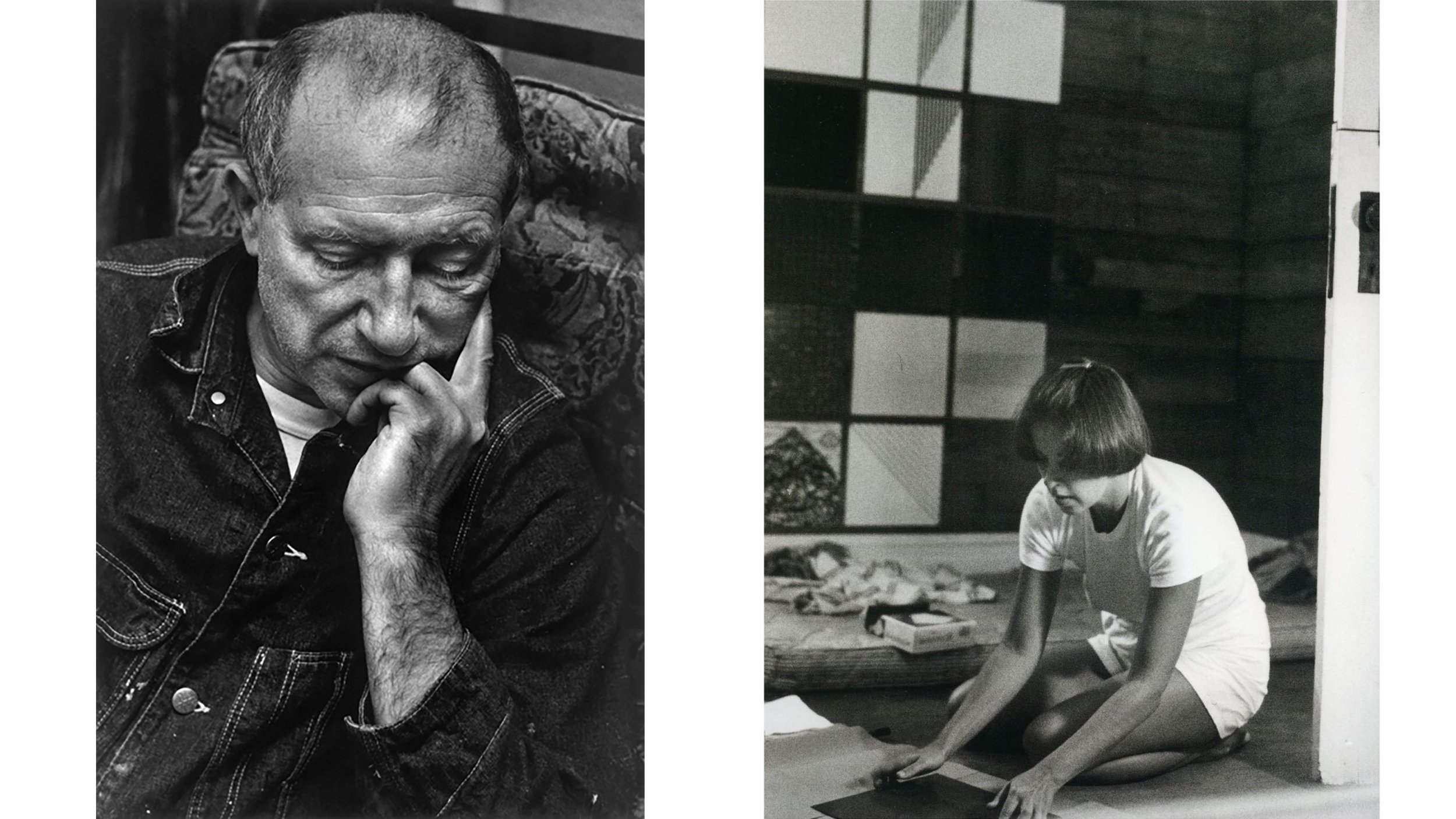

Portraits of Jennifer Bartlett and Jack Tworkov by Arthur Munes, c. 1975. Courtesy Tworkov Family Archives

For Jack Tworkov's birthday, August 15, and in celebration of the life of Jennifer Bartlett who passed away last month, we present this recently discovered audio of a lecture Bartlett gave on Jack Tworkov on the occasion of Tworkov’s first posthumous retrospective curated by Richard Armstrong at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in 1987. The following is a transcript of the original audio from a cassette tape made available through the archives at PAFA. Due to the degraded quality of the cassette, the transcript has been edited for readability and in those instances where audio was indecipherable, marked “inaudible.” Special thanks to Hoang Tran, Director of Archives at PAFA for his assistance.

The friendship began at Yale School of Art and Architecture in 1963. Jack Tworkov was the Chair of the department and Jennifer was a student. Beyond graduate school, Bartlett became close to Tworkov and his family, visiting with them frequently for long stays at his home in Provincetown. In 1973, a two-person exhibition of Tworkov and Bartlett’s work opened at the Jacobs Ladder Gallery in Washington, DC. They exchanged gifts of artworks: Tworkov receiving a drawing for Bartlett’s epic “Rhapsody,” and Bartlett receiving an early work from Tworkov Abstract Expressionist period. They remained friends until Tworkov’s death in 1982.

News clipping advertising the lecture in The Philadelphia Inquirer, Tuesday, March 24, 1987.

-

One of the series and programs we've had in relation to Jack Tworkov Paintings 1928 to 1982, and this very informal program. It is a conversation with Jennifer Bartlett, who is a friend of Jack Tworkov's, and she was also a student at the Yale School of Art and Architecture from 1963 to 1965. She received a BFA, MFA when Jack Tworkov, who was chairman of the art department there. The setup this evening is that Ms. Bartlett will talk very informally for a few minutes, maybe ten minutes and then perhaps there'll be some questions from the audience and if there's time we might go upstairs and look at the paintings which are displayed by year. I just want to say a few words about Ms. Bartlett. She recently showed a major show at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York and she’s received several awards. She was also only perhaps of the half a dozen women who were recently represented as part of the Carnegie International Show. So she is a preeminent artist and preeminent woman artist to have visited [inaudible 00:01:25] national celebration of art for National Women’s Month.

I also want to mention that Ms. Bartlett has declined to take a fee or for coming down on a very tight schedule in New York and as a result of that, we do not need to charge a fee for this talk this evening. So, for those of you who would like to have a refund are encouraged to pick up a refund at the desk on your way out or whenever you feel like it. So, I want to thank Ms. Bartlett very much for taking the time out of her very busy life to come and talk about New York and Jack Tworkov.

Jennifer Bartlett:

My first memory of Jack was with his wife Wally. She was one of the most sensational cooks; she studied with several people and was absolutely perfect. No matter how perfect she was, Jack could always find something that could be done a little more purely. And I remember a very long, quite hysterical talk in their kitchen in their house in Provincetown, about which way you take off the skin of garlic. And after garlic, exactly how many cloves of garlic there were too each tomato - tomatoes of a given weight and certain ripeness.

And there this spurred during this cooking period for this [inaudible 00:03:49]. Depending on the kind of pasta you were putting it on top of in other words the sauce would simmer for, and possibly make more rigid surface that would catch more sauce. And in some way, the three or four hours were spent in this discussion about garlic despite much of Jack to me. He was a man who was absolutely fastidious by nature and incredibly reserved, yet could get wildly excited about a new way of counting if anyone told him. He was the kind of person that would give me a gift basket, “I don’t trust the Fibonacci series of numbers," at one point. And I told Jack, "Well I would just use them quite callously in about 30 pieces." And Jack went downstairs, I was staying with him at his summer home, and there were volumes on the Fibonacci series. He was relating somehow the move of knights in a chess game. He had extended this line of thought to a point that I couldn't even have anticipated.

Why not give me credit for not only introducing him to the idea but practically inventing it. Yet he in fact became the expert on this series of numbers and his research permeated every aspect of his life. For example, he didn't read novels. This was always a great moment of contention between us, because I read novels constantly, and I'm very, very bad at non-fiction. His wife reads novels. His sister, Biala, was married to the novelist, Ford Madox Ford, which I found of course enormously glamorous. And wanted to talk in great detail about it with Jack. I wanted to know what they were like, what happened, how did Jean Rhys screw up the relationship, and all the sort of the things, the literary talk that I enjoyed so much. Can you hear me without this? I usually have a very, very loud voice.

And so Jack was of course appalled by my request. He was completely disinterested in the subject. He felt that if he read novels, he would have absolutely no time to learn anything about life whatsoever. He was a firm believer in approaching bodies of knowledge—calmly looking through and seeing their shape and it wasn't to be neglected.

And I remember he considered his greatest vice, reading newspapers. He was absolutely crazy about the newspaper. But he only allowed himself one in the morning, I think an hour and a half of going through The [New York] Times. Because he didn't feel that they were really read. So, every column had the same amount of attention that any other column would get. [inaudible 00:06:51] some research into back issues to see if the articles were in fact developing a theme of thought. And then address them if they weren't.

Another thing I can remember of him, what he did at Yale was quite extraordinary and I was there, fortunately at his first year. And I thought it's nice to say this of an institution [inaudible 00:07:17]. Yale was going through a period of quiet [inaudible 00:07:22] because there wasn't a lot happening. And Jack has always put other people before himself in some ways, he likes to be an impresario I think, rather than the star. And I mean this as a quality of quiet modesty that comes very, very, very much through his work. And what he did at Yale, was invite down a number of people who were working in New York at that time, quite young: James Rosenquist, Rauschenberg, Jim Dine, Bob Morris, which was enormous, and they came down and talked in the straightest fashion six-week course, but they would just come down for two or three days.

There were many marvelous teachers at Yale at that time and I think Jack's contribution of throwing together a faculty that was stable, and this was really before the big visiting artists programs like what we have tonight [inaudible 00:08:28]. So, he threw together a stable of faculty and a faculty who had chosen not to teach essentially. I think the conflicts between them, the congruences between them gave a lot of weight to both points of view. Because it was one thing to have your drawing instructor say, “That was a terrible drawing, it's very boring, it's bad.” And you can go up to them and go, "Well, I'm going to New York and I’m showing with Leo Castelli in six months, so what do I care?” This was the idyll of the students at the time [inaudible 00:08:59]." Then you go over into your studio and Jim Rosenquist says the same thing. There was a kind of reinforcement that I think provided a very, very good education. And, in the meantime, Jack was behind all this, being an iconoclast.

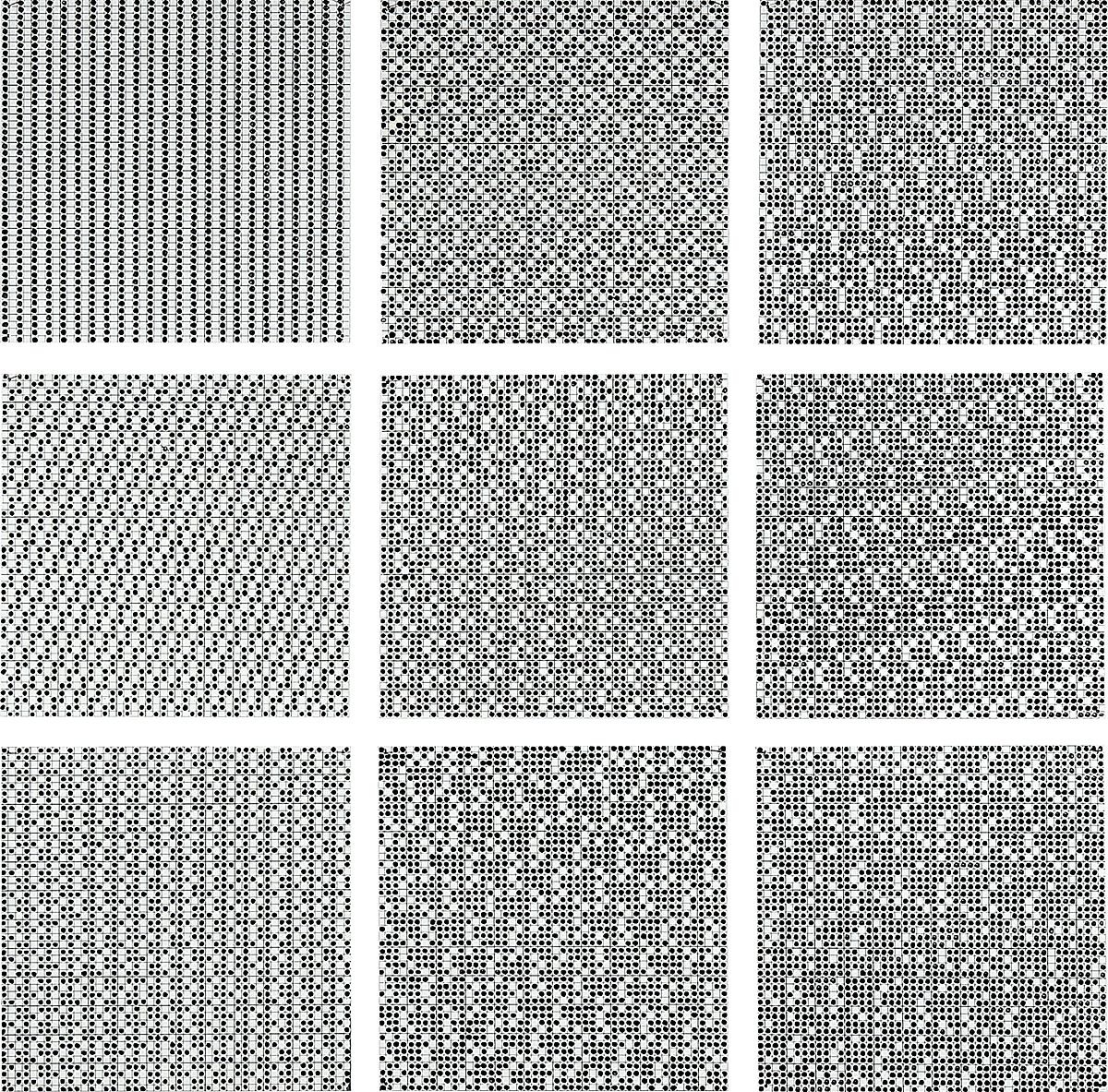

This work on enamel plates by Jennifer Bartlett titled Count, was a gift to Jack Tworkov and remained in his family collies collection until 2016.

I remember at that time; Yale was a three year program and Jack just kept ignoring his classes. [There was] a strict hierarchy. All the best third year students would be at a place now called Crown Street / Prime Street. That was Richard Serra and Chuck Close and Nancy Graves. First year students [like] myself were caught in cinderblock cubicles with six-foot ceilings! And there were various stages in between the hierarchy. And say if there was a visit from Rauschenberg for all the third-year students [inaudible 00:09:56] exhibitions in their rooms, and Jack might not ever take them to Crown Street, he might not have thought they deserved the attention, he might take them over to take a look at the first-year students. And I could remember when he did that for me, I had come to Yale from California and having somewhat of hard time adjusting to the East Coast. And feeling safe making larger canvas blocking out all of my studio [inaudible 00:10:35] And at this glorious point, Jack brought Rauschenberg by and said, "Oh Gosh, that looks like a Picasso." Of course, I fainted with joy and ran through the building and spent the next six months trying to decide whether it was a compliment or not!

Jack also accelerated a few things [inaudible 00:11:00] I’ve always been sympathetic towards a person who can never learn to ride a bicycle [inaudible 00:11:08]. My academic merits [inaudible 00:11:12] with the greatest spirit of gusto and trying to avoid threats, which Jack happily cooperating. And so instead of having to say three years, one could say, two years [inaudible 00:11:31]. So, he was constantly bending rules. And I think that's because I think the school as an institution had almost no reality [inaudible 00:11:39]. It was a place where older painters and more experienced painters and authors and artists, were just starting out. And I think that was the structure has he ever gone [inaudible 00:11:54] school. And I think it's quite a difficult notion. And I know that Jack's interests continued in young people, far… Up until the day he died. There was always something during the 21 years, he was interested in was school. Most marvelous work. And I think that’s a beautiful notion. [inaudible 00:12:08] he was interested, and I kept getting this phone call [inaudible 00:12:16] work. And [inaudible 00:12:20].

He was always interested in me of course and one of the sad, sad things about Jack is in the kind of age [inaudible 00:12:38] he had many great supporters, but his reputation is more secondary than it warrants. In other words, I read in The New York Times by a great friend of mine, John Russell, that Jack was a second generation Abstract Expressionist. Jack wasn’t a second generation Abstract Expressionist. He was a first generation Abstract Expressionist.

He had a studio right next to de Kooning, they were all sharing but a very strange thing happened [inaudible 00:12:58] the nature of the character with Pollock, with de Kooning, with Franz Kline were all opposite temperaments of Jack. They were all flamboyant, heavy drinkers. I mean, Jack always spoke to me, he told me that de Kooning, whom he admired enormously and cared about very much, was an alcoholic by invitation. That was the first time he did it [inaudible 00:13:41]. And when de Kooning first came, he was just like a Géricault. He was so pure and fresh with incredible skin. You took one look at Jackson Pollock and oh my God. This is fantastic. So there was a whole sense of fear, which isn't written about, but everyone recalls. [inaudible 00:13:57] Their time off was as important as their time on. Their meetings in the studio were important. All of that was important. And I think Jack was someone who kept doing his work, it would fall where it would it certainly has very much the same exceptional emotional basis, I think of any of the other Abstract Expressionists, but it was also quietly.

And I remember one of the most shocking, I think the most shocking thing that Jack ever said to me, was… I had been describing a body of work I was standing on, I said, “Ok, 2000 feet and this is going to be 800 feet long and I've got a grid coming down. And then someone comes in the door with a large horn and a thing of caravans coming in and [inaudible 00:14:38]."

[And Jack asked] "If I ever [could see] how the person who would walk into the work [inaudible 00:14:49]." And I was so startled [inaudible 00:14:53]. I knew [inaudible 00:15:02]. And [inaudible 00:15:03] truly humiliating, and I said to Jack, “Yes I don't, Jack, but I'll think about it." And I think that that truly was Jack’s goal in his work and as a person, was that somehow the scale centered the storm. That the important things in life that were interesting to Jack [were] infinitely wide and almost imperceptible. I remember talking to him once about happiness. And he said that he had no idea about it. He said that happiness for most people had come at the most extraordinary times, and maybe you've gotten up fifteen minutes early. And performing [inaudible 00:15:48] and it sounds a certain way. And there was a feeling of happiness. But the moments can't be cared for, that they aren't related to reward or to the brain. You know… the joys in our life. But they come in a very still and silent way. And they're very, very brief.

Left: Portrait of Jack Tworkov, c. 1960. Photo: Marvin P. Lazarus. Courtesy Tworkov Family Archive.

Right: Portrait of Jennifer Bartlett, c. 1975. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

I can remember going to see Jack the day before... I guess about three or four days before he died. And he was lying very still. Very, very, ill in his room. And his one great concern, let’s see... whether I was there or not was not very important. But the shade was not pulled down at the proper angle with the proper amount of light coming through. And there was a kind of an agitation, and his daughter Hermine came over to fix the shade, and there was a feeling of peace in the room. And that's really what I have to say about Jack.

I wonder if you have any questions for me. None? I think that this is the most stultifying boring experience [inaudible 00:17:03] Maybe we’ll double your money back.

A friend wrote me up today about a lecture that the film maker Jack Smith did. And he went and [inaudible 00:17:26]. Anyone in the audience could ask questions for 25 cents and answers cost 50 cents. And this was a very trusty proposition because if you were practicing a question that was worth 25 cents, maybe the questions would be a little bit more radical since you were paying for it. You felt you had a right to be nosier than you should. But we have absolutely no questions here.

Question 1: [inaudible 00:17:59]

Jennifer Bartlett:

I don't even know if Jack ever mentioned the West Coast [inaudible 00:18:22]. I don’t think I know if he had ever been to the West Coast. Do you know if he had been to the West Coast? I forgot to ask, that’s very interesting, because I think it was [inaudible 00:18:26]. In my relationship to Jack, I think he laughed once when I said I was from California. And that was the extent of the entire thing. Because he had always had that long commitment to Provincetown. And I think that was quite enough for him. You know his grass wasn’t large in that kind of a way. I don't ever think of Jack as being much of a traveler, when I think about it. He was really home with his wife and two children. When they left, he led an absolutely regular life. They would have guests once or twice a month, and they would go to Provincetown in May and stay through September, October. But that is an interesting question, because I realize that his life as an artist is so different than our lives as artists. We’re part of the, right now, the hideous busy generation. And I think the conversations are just measured in terms of who’s busier than whom. But Jack really didn’t travel very much.

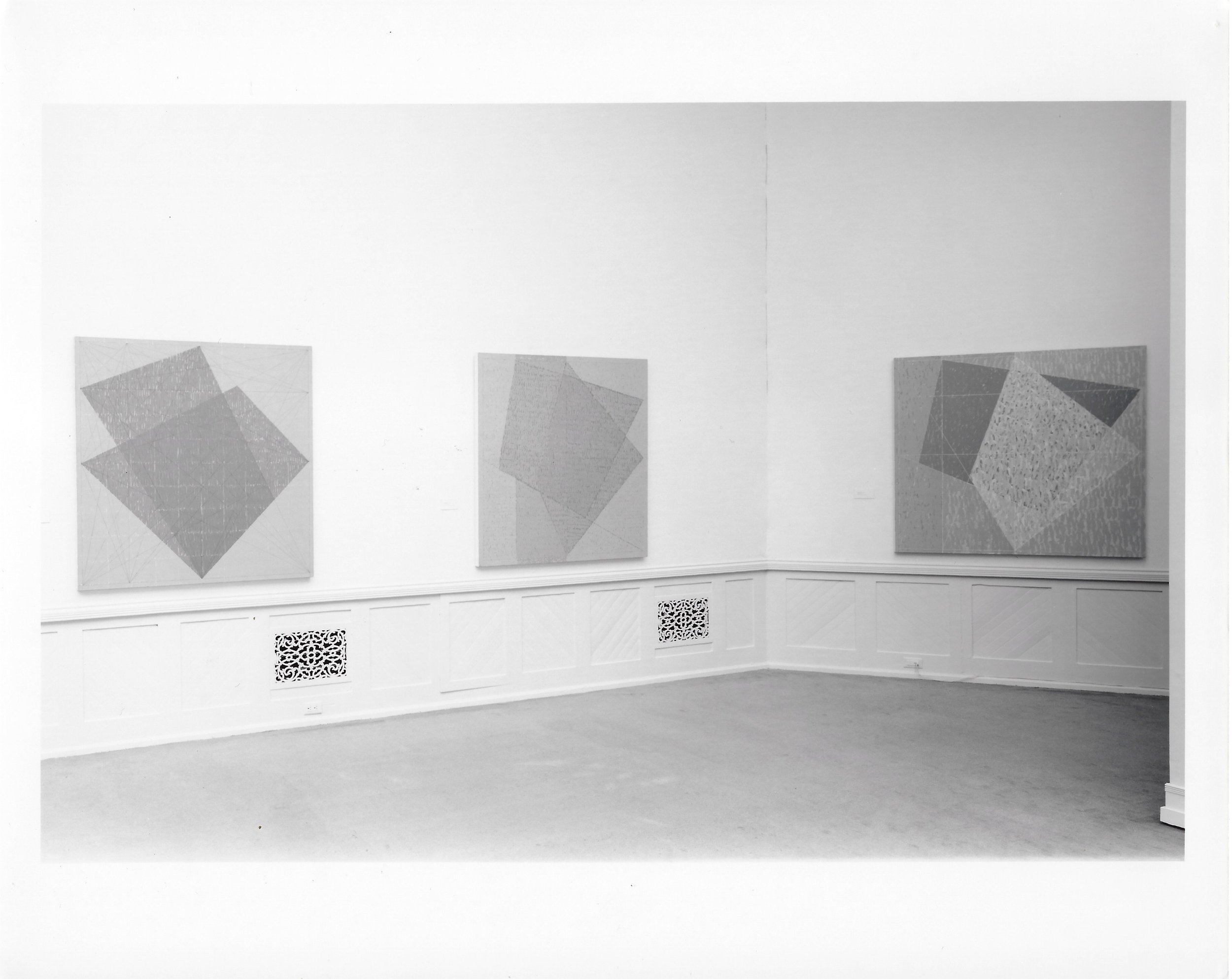

Jack Tworkov, Idling II (WNY-70 #1) [CR101], 1970

Oil on canvas

80 x 70 in (203.2 x 177.8 cm)

Collection of the Estate of Jack Tworkov, New York

Question 2: [inaudible 00:19:35]

Jennifer Bartlett:

He talked at one point when he was just using the grays, he talked a bit about that, but they were never just grays to him. What I remember, there is a painting that I have, it’s an early one, and each gray is kind of different, one’s really a pink, one’s really a blue, one’s really a green. So, I don't think the palette has so much changed as heightened in one direction or another. You know when the color would come and... Now in the end, when he was almost... His imagery in some cases was getting... What he was working on, his son in law, what Bob Moskowitz was working on, seemed to have some kind of similarities to me... Do you know what I mean? Those kind of searchlight images and the beam images... And how within this structure there would be a real contrast and edge between color. It wasn't one of those floating veils of color but a real thing of drawing. [You] asked me if there was a kind of radical change in palette... You know I had never talked about that, but I have a feeling it was really dictated by a tiny part of form and a specific form on the canvas not an overall. It was even really a bit like some of the early earlier "Barrier" paintings.

Question 3: [inaudible 00:21:18]

Jennifer Bartlett:

I haven't used it for years. I was doing, working at the time on the baked enamel and clay, that’s when I was starting this counting. And mine was all really just counting. Or I would set up things up using that numbers situation because the jump was interesting to me. Jack would plot things. And I don’t even never know how he was using Fibonacci... he was hopelessly using [in his] painting... he would take certain measure of the edge of the painting and the painting would be selected because of the size. And then there were points, and the connection of the points would be a Fibonacci number. So he organized his picture plane, and I would more start from left to right until my paint dried... Anything else?

Question 4: [inaudible 00:22:26]

Jennifer Bartlett:

I agree with you and I think there was a kind of a time thing in a way that wasn't that quiet. It wasn’t appropriate at the time... If you think of the paintings of... of that... the big floating color blocks... Rothko. And I’m supposed to be the sort of artistic expert here! In the way of Rothko, where they were incredibly sort of sensitive, sensual, exquisite surfaces. But I've never seen a Rothko painting... even the darkest brown... that's sole intent to me is wrong. They're all extremely dramatic. And they are all extremely, incredibly physical and sensual. And Jack’s paintings, I think, involved something different from that... He wanted to keep a kind of puritanism in a certain way. He wanted to keep a real balance between thinking and consideration. This may explain some of the colors questions someone asked... of thinking... of something cerebral over something that was much more sensual or physical... and it [steer] him when things got out of balance... out of fear of going one way or another. And I think the best kind of drama that goes in it or on it in some things [inaudible 00:24:39].

I also want to say the question made me think of Jack's studio. And then when Jack died, well we brought together all his brushes, and everything was kept absolutely perfect. And was giving things away to different friends of Jack’s and I got a terrific chalk drawing from about 1946. That is serviceable. But also, a brush that I still uses. All his brushes he will take and shape differently. He would buy regular standard oil bristle brushes. And he shaved his own filberts this shape. He shaved his own [inaudible 00:25:24] brushes.

But I have this extraordinary one. It's a perfect cone and it's kind of a hard cone. And so, he must have used this for lines and for points, like that. But what I can't figure out is how perfect he got the cone. I mean he must have had to work for hours and hours and hours to get this coming up like this and it still works.

Question 5: [inaudible 00:26:01]

Jennifer Bartlett:

I think sometimes they are. That they have been marked into the painting. We can go upstairs and look up there.

Question 6: [inaudible 00:26:14]

Jennifer Bartlett:

Well, I don't really see the change. But I'm very, very bad at things like that... same exact thing with Rothko, Clyfford Still, or any of the Abstract Expressionists... certainly with Pollock, they had very layered methods of work. I don’t think really they changed radically... I’m trying think of any changes, but I don’t see that.

Exhibition announcement:

Jacobs Ladder Gallery, 5480 Wisconsin Avenue, Washington, D.C., Jennifer Bartlett and Jack Tworkov, June 9–July 7, 1973.

-

In Autobiography* Jennifer records a daydream: with the bases loaded she hits the ball out of the park. Stan Musial has been watching her. "Who is that girl?!" he exclaims.

In Cleopatra* Jennifer writes, "I'm Cleopatra, this is my room I want whales swimming in oceans not fish in streams.…” "Again" Cleopatra, generating, fusing and linking, was an energy warehouse with more than one outlet."

A friend comments, "she writes wet but her paintings are ... cerebral." Leonardo Da Vinci asks "who is that girl?!"

Jennifer writes out number programs on paper, progressions, limits, summations. The baked enamel grids on steel plates contain 2304 squares. Progressions are marked with dots painted by hand in enamel. The consequences are unpredictable images sequentially changing shape and in motion from plate to plate. The whole series becoming a cinematographic unit.

I LOVE AND AM REFRESHED BY AN INTELLIGENCE TRANSFORMED INTO POETRY AND POETRY TURNED INTO NUMBER

*Jennifer has so far two books in manuscript form circulating among friends, Autobiography and Cleopatra.

-

"In the end, the work which I have exhibited contains, I believe, an element of self-portrayal which for better or worse I can reconcile to myself without embarrassment. I would not be comfortable with a painting that was too aggressively stated or too sleek or too self-consciously simple, or too beautiful or too interesting. I am uncomfortable with extreme portrayals. I let reason examine disorder. A certain amount of censorship results which one could call form."*

*from a statement by Jack Tworkov

Question 7: [inaudible 00:27:08]

Jennifer Bartlett:

[inaudible 00:27:12] the year I stopped smoking. [inaudible 00:27:17] in August he started again. And I was just thinking and have to stop all over again. I was thinking how I was going to greet everybody [...] Jack was during that time of not smoking [inaudible 00:27:40]. He was almost completely supportive, and he was always completely vague. [inaudible 00:27:47] I was having a conversation with Jack [inaudible 00:27:49]. And then you realize something’s come unraveled [inaudible 00:27:57]. And look at you and you have no idea what [inaudible 00:28:19]. And this [inaudible 00:28:20] was a part of this teaching style. It was all [inaudible 00:28:27]. But I certainly don't have [inaudible 00:28:30] of Jack being [inaudible 00:28:37] work or a point of view and becoming quite angry. He wasn't an angelic man in that sense. I think he was very controlling. At the same time of the people around him... he was extremely complicated. But he had a real vision of what he wanted his life to be [inaudible 00:29:02] a year and a half. And so just as long as [inaudible 00:29:19] you walk over to this table and [inaudible 00:29:20] like that.

Another thing, but [inaudible 00:29:25] that are very, very fond memories for me is getting up at six o'clock in the morning and go for long walks. Three-hour walks at a very fast pace through the Truro and Provincetown dunes. And he knew every sort of inch of that [inaudible 00:30:04]. And also he liked swimming [00:30:12].

Question 8: [inaudible 00:30:19]

Jennifer Bartlett:

[inaudible 00:30:32] Jack was interested in Classical painting and in value painting. And I don't know if you've seen the drawings in the show... absolutely beautiful, marvelous drawings from all periods of his career. I'm trying to remember who he... At the time that I knew him, he was already sixty-five or something like that. So, he was past the point of view where you're talking about other artists. I think that occupies until maybe 35 years old max, if you've been working hard. And then you forget about it. And it'll come up in a kind of conversation, a particular painting. But it will come up in the way that come up with any painters who talked about the Van Eyck altarpiece for a reason. But it wouldn't be... I wouldn't have conversations like who do you think is good... who influenced you... that kind of thing. Because that's always a hard question to answer, I think for any artist. Particularly with our ego. Because obviously the first to influence them is them [inaudible 00:31:43]. So, I don't hope for a lot of accuracy with these answers. I know that he [inaudible 00:31:54] public airing and respect. I think with Jack was very, very conscious of people sometimes were underrated [inaudible 00:32:16].

Question 9:

In our catalog, there's only one photograph out of many new photographs of Jack that show him laughing along with his grandson Erik. And then you mentioned his chuckling at your statement. I'd love to know what his sense of humor was like. What did make him laugh?

Jennifer Bartlett:

[inaudible 00:32:39] remember, Jack wouldn't be the kind of person who would laugh if someone slipped on a banana peel. So, one aspect of his humor, I think, was quite broad. He loved early comedy... like Charlie Chaplin and all those early comedies enormously. And I think he would laugh whenever you were silly. But I don't remember Jack, being a person who would make jokes or make wisecracks or witty, clever remarks. He was kind of a very appreciative audience of everybody else’s antics. And his laughter was not always of the gentlest sort. I think.

[What] he really did read and think about and talk about incessantly were... “Ulysses” by James Joyce and "Finnegans Wake." And Jack was a real modernist in a sense, and a very committed modernist, and he liked work... and I remember this now he always liked the work of Ford Madox Ford because he thought that he was reactionary. And he thought that work was being done in fiction was so much greater than that. He would be interested in those fossils for that reason. And if he did have a real commitment to the development of thought in the world.

Question 10: [inaudible 00:34:19]

Jennifer Bartlett:

Perhaps he felt everything was suitable to a degree and then by the time I [inaudible 00:34:28]. Go ahead.

Question 11:

I think is is kind of like a People's Magazine question, but I keep thinking of your wonderful story about the window shade. Did he make that request because he wanted the light coming through or because of his [inaudible 00:34:55]?

Jennifer Bartlett:

I just think that to be honest, that was really what Jack had to look at and what he wanted to look at, and he wanted it right.

Question 12:

Do you think Jack will be remembered more as a philosopher or as an artist?

Jennifer Bartlett:

Those are hard questions that you ask. It depends on so much that the audience… And that was another thing that I was going to share. I think the audience... In the latter part of Jack's life, was looking for something different in a way than what he presented. Forecasting a strong relationship to say Ellsworth Kelly. And to the minimalist thought [he] is really quite important in terms of minimalist thought very early. Yet it was a little too dangerous for the direction that whoever got [inaudible 00:36:02]. But you know, these things get sorted out. I could imagine showing this... who lives in New Mexico, woman... Agnes Martin! Jack. Really, I somehow see parallels. The other day, my husband in Spain, father of my daughter. [inaudible 00:36:27]. I'm blanking out constantly. Agnes Martin and Jack could be quite interesting. I think that those things get sorted out and then you have exhibitions like this… and their opinion changes… [inaudible 00:36:46]. Because look at what happened to someone like Paul Klee. Nobody except college students had really thought or talked about Paul Klee in the last five years that I know of. And then [suddenly], there's a huge show in New York. I got to remember [inaudible 00:37:04].

The leaps and bounds with which the art world roam all over the world... I mean, we are proliferating like rats! I think there's probably one artist practically for every five citizens. Rather dangerous situation. And I think that we forget a lot or that we aren’t, we’re just not… maybe he isn’t coming to mind to the scene at that time or to curators, and then someone does an incredible show... brought into new light... They could be [inaudible 00:37:43] so I think. But we don't know I think we don't know. Any other questions?

Jennifer Bartlett’s Drawing for Rhapsody (1976). A birthday gift to Jack Tworkov’s wife Wally

Question 13: [inaudible 00:38:03]

Jennifer Bartlett:

Yeah. Because I think he was just... what he was astonished by... is the arbitrary quality of mathematics. In the work and so [inaudible 00:38:24]. I think it was that his was the interest was that mathematics was not actually about numbers or something like that. But it actually was a language to talk about things that could not be expressed in any other kind of language. And that has baffled me on all sorts of levels. [inaudible 00:38:51] that really [inaudible 00:38:50]. I mean, he would be very amused [inaudible 00:39:01] recently [inaudible 00:39:05] say, [inaudible 00:39:07] the physics [inaudible 00:39:10] just turned into a complete math class where within six hours of doing seven [inaudible 00:39:18] because maybe they've raised a summary about doctors that's never been know... we've actually changed all aspects of technology. You can remember that the same thing happened [inaudible 00:39:24] years ago, when [inaudible 00:39:24] space for at first being thought about trying to find [inaudible 00:39:24]. I didn't [inaudible 00:39:24]. And finding [inaudible 00:39:24] Fibonacci discovered in the 14th century, 15th century. And it's numbers appear in how a pine cone grows... the number of [inaudible 00:40:10] in the world of sea shells... and the orbits of planets. And these number all seem like Fibonacci numbers. And but I don't know why. So, I think that probably this is all [inaudible 00:40:29]. Any other questions? Yes.

Question 14: [inaudible 00:40:38]

Jennifer Bartlett:

I supposed he would have, but I've never been one for discussing work. I like sort of the more pragmatic... If he would have asked me what I thought about something I would have answered. But I can't imagine myself in conversation sitting down with another artist and giving them a crit. I’m ultimately a great disbeliever in crits after you have left graduate school. So [if one] would try and come around and say, “Oh would you come to my studio and give me a crit…”. I find this singularly bad taste for an adult. Sort of like blaming your parents for everything’s that happened to you after the age of 21! Yes, it hurts. Anything else?

Question 15: [inaudible 00:41:39]

Jennifer Bartlett:

There weren’t many of us but Jack…

Question 15: [inaudible 00:41:42]

Jennifer Bartlett:

What?

Question 15: [inaudible 00:41:46]

Jennifer Bartlett:

Well, certainly not. No. [inaudible 00:41:53]. No, I can't really speak to [inaudible 00:41:56]. Jack always treated me with great feel and courtesy.

Question 16: [inaudible 00:41:56]

Jennifer Bartlett:

Yeah.

Question 17: [inaudible 00:42:00]

Jennifer Bartlett:

Yeah. I think it’s much easier to start out in this world as a man than as a woman. I think if you’re a white man or a white woman, you're luckier than a black person trying to be an artist. He has a lot of that [inaudible 00:42:57]. And it's possible for a period of time to really step back and narrow in on one issue... very thoroughly before you move to the next [inaudible 00:43:26]. And that kind of overall long-term vision. You know, not this show, not the next, not this and not that. But then the long-term idea of what you need to do as an artist to develop your work despite what's happening outside. And sort of be prepared to take responsibility for that. Which is, I think is something Jack would [advise].

Anything else?

End [00:44:11]