Interview with Jack Tworkov (Feb 1979)

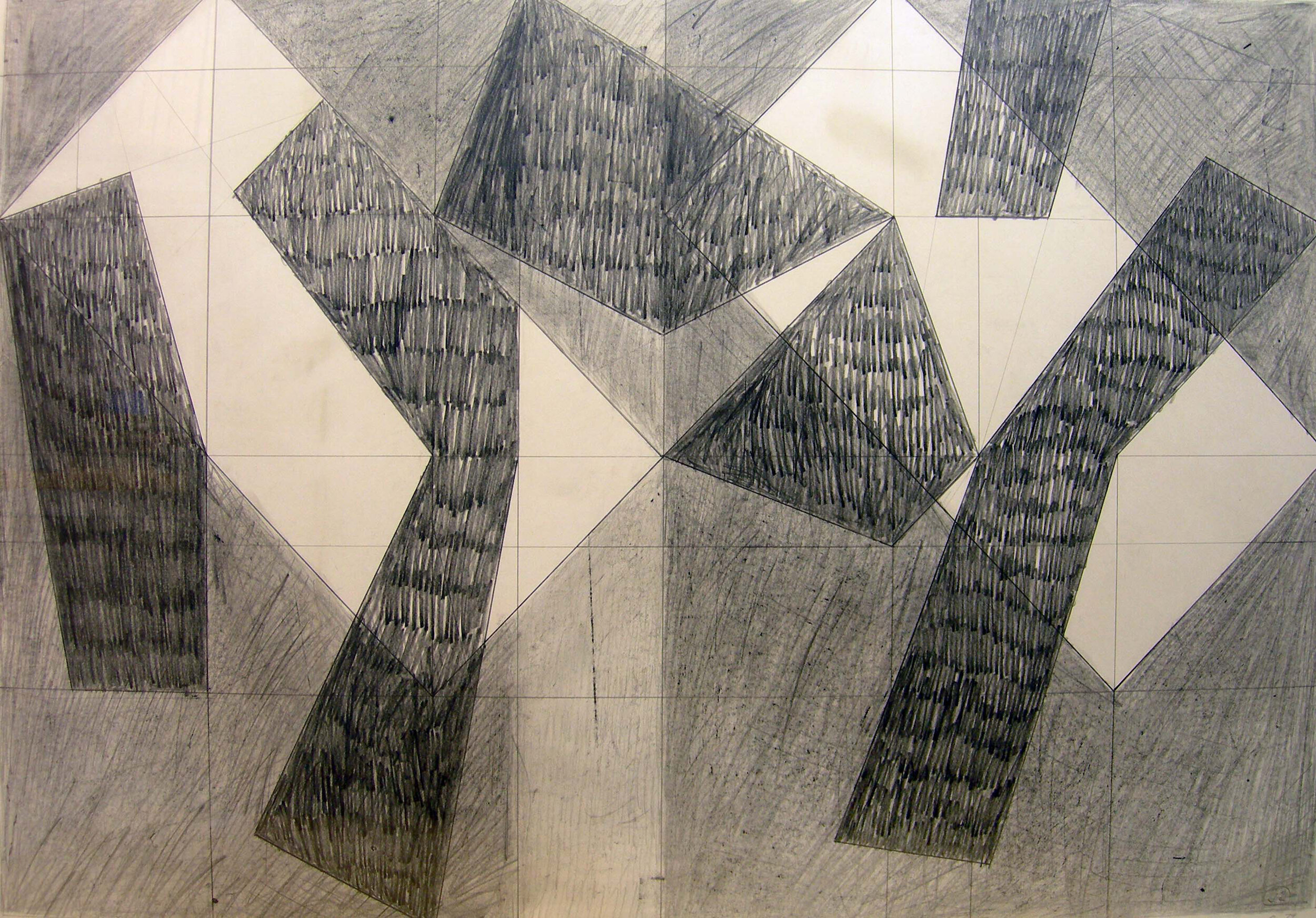

In February, 1979, Jack Tworkov was a visiting artist at California State University, Long Beach. On February 24, 1979, an interview was conducted by Susan Manso. The transcript, herein is edited for readability and begins at [00:00:45]. The interview captures Tworkov’s honest and insightful responses to a range of questions from the conflict of subject in abstract art to the ruling ego driven careerism in the art market. Tworkov comments on his involvement with the WPA and the optimism and then disillusionment Post World War II, all of which fueled the development of The Club, of which he was a founding member. The discussion about creativity and the desire for uniqueness is particularly revealing as are Tworkov’s feelings regarding his friend Mark Rothko. A series of drawings, created during his time in Long Beach, illustrate the interview.

Susan Manso [00:00:45]: Okay. My first question, I try to organize it somewhat, but I think this question of the painted subject is [crosstalk 00:00:53]. And a while back in 1973, Art in America published some notes on that painting, in which I put ... You'll see where there are one or two ellipses:

“One could trace the development of abstract painting by following purely formal development step by step.” I dropped a sentence or two there. “Nevertheless, I sense that a social, psychological element was all the same present in this development. It strikes me that this element was the vacuum left in western art by the emptying out of the religious and mythical element, which had provided the essential ground for significant and believable subject matter. There was nothing in our century to take the place of the universe, the significant and believable subject matter. Although Marxist artists thought there was, they could not develop a meaningful iconography, only banal clichés. This led to the emptying out of the picture of all exterior reference, leaving it to the still and movie camera, for record and comment.

In a sense, the abstract painting, which most typically represents the iconography of the post religious age, consciously or unconsciously, expresses an element of despair which runs like a thread through our century. Which is an ingredient in the most serious abstract painting. I sense it in my own work, as I do in [Jackson] Pollock, [Willem] de Kooning, [Mark] Rothko, and among the younger painters, [Jasper] Johns. Classical art that was a face-to-face dialog between artist and patron. It was the patron that most often determined subject matter. In market the anti culture, this has become all but impossible. And if it were possible, it would be destructive to let the masters of the marketplace decide on a canvas; better, the empty canvas.”

Susan Manso: Well, I wondered if you put …

Jack Tworkov: Is that the way it is written there, the size on the canvas? Or there's something left out there, besides on this subject, probably. That did not serve [crosstalk 00:02:57].

Susan Manso: We might have it. I typed it this morning.

Jack Tworkov: Let the masters of the marketplace decide on the subject, on the subject.

Susan Manso: Well, I can later check it and see if I've made a mistake. I don't have the …

Jack Tworkov: Yeah, okay, but I'm sure there's something wrong there.

Susan Manso: Yeah. I just typed it wrong, and [crosstalk 00:03:25].

Jack Tworkov: Yeah.

Susan Manso: I wonder if you could at all elaborate or comment on the element of despair.

Jack Tworkov: I've already said it as clearly as I possibly could. In other words, would be emptying out of the subject, also with the disappearance of the relationship of the artist to a cohesive culture, a cohesive belief or anything like that. The artist did draw upon himself for his subject matter and became the individual as an art develops from that date on. Expressed also by a kind of Bohemianism because the artist was almost separate from society.

Well, this was not the happiest thing for the artist to happen. The artist, in a sense, works in a void, depending entirely on intuition prompted by self, et cetera. But he misses the connection between self and the world, and the cooperation of the other artists, as it existed in an earlier period.

In the birth period of art, you don't find art as striving for uniqueness. They strive for excellence. They don't strive to be ready to stand out at any cost. And, I think this is cause enough for despair, but also the century was a horrible century. I mean, horrible wars and horrible persecutions and so forth. It's hard to raise up human art at such a high level when human nature is so vulnerable.

Susan Manso: Yes.

Jack Tworkov: And so you really had the empty canvas sometimes. It really spoke of emptiness. It was really a ... the same element much like existentialism, when they speak of nothingness, in existentialism, which also is an element of despair in the writing of some of the existentialist philosophers like [Martin] Heidegger, [Jean-Paul] Sartre and those. So I don't think it's anything unique that I said. I think it's very obvious.

Susan Manso: No, I didn't think that it was a ... I just wanted it super clear. This despair has something to do with putting a great burden to put on the self.

Jack Tworkov: Yes, I think it's a ...

Susan Manso: What I'm trying to get at is, there's a lot of talk ... It seems to me that one of the things in talk about abstract expressionism, when it gets to what the subject of the paintings are, I think it gets a little bit muddy. And in a way, I believe that in some of your own statements, you would somewhat dismiss the idea that the subject of art can never just be the painted soul or psyche or self. But exactly what… how we can talk about the subject of art ...

Jack Tworkov: I mean, the subject of abstract paintings is the absence of subject, in a sense. It's the absence of subject. The artist acts in this painting like a dancer, for movement's sake. Out of instinct that his own body, and so forth. And there's a symptom of that pleasure and there's a symptom of that meaning to that, an unbearable meaning. But it's very difficult to connect this to a ... Well, if you compare it, say, to the movements, or anyway to the possibility of a movement, this can have such a wide range of seeing, such a wide range of reaction there to the world, painting is … It's impossible for painting anymore to do that.

There was a time, however, when it expressed itself to give a subject matter. That is, the subject matter was set by the church, by the nobility, whatsoever. The artist really didn't choose the subject matter. But he strove for excellence in doing that. His genius lay, not in invention of new painting, but in how great a painter he really was. That too also established, say, standards, such an artist could live and could measure himself. Today, there are really no standards. What is the vision? The critic says this, the other museum does this. There is no standard, since everything under the sun was possible. And in fact, in our time, the art that abandoned any kind of standard, has abandoned any kind of … values, it was the avant-garde art. So that's it. The possibility of positive feedback in our time, for an artist is very small. He practically has to find it entirely in himself.

L. B. Pencil Drawing #2 (CR 191), 1979, Pencil on paper, 20 x 28 3/4 in. (50.8 x 73 cm) Collection of the Estate of Jack Tworkov, New York

Susan Manso: Okay. I think that answered this first question, so I'm going to skip them. Just for the record, I'm going to ask for one second, a little bit about Greenberg and Rosenberg, since those two ... Sorry, they just got a little stuck together. Do you think it's particularly useful for Rosenberg and his action painting, Greenberg and his art is about art? And, well, I don't have to summarize for you what the two ... There are two kinds of approaches.

I personally feel more sympathy for Rosenberg, but I don't see how either, except in Rosenberg insofar as over the years he subjected something of a temperamental spirit connected with a lot of the late '40s, '50s. I don't see that those populations are particularly useful in understanding or enjoying ... I'm answering instead of asking you, but I wanted to know what you think.

Jack Tworkov: Well, the truth is, I haven't heard them so far. I don't know their writing so well. I knew Rosenberg fairly well, better than I knew Greenberg. But, in both cases, they made their application and fixing their focus on a number of artists. And, made their criticisms to suit the artists that they liked.

Susan Manso: Uh-huh (affirmative).

Jack Tworkov: And … I don't know enough about them to really be able to comment on their philosophical point of view because I haven't heard of it.

Susan Manso: Talking about the '40s in art, Philip Guston, I think he said this to Dore Ashton, she quotes it in her book, yes, but, had said that the officials have talked about the curative style but it was, I quote, "A revolution that revolved around the issue of whether it's possible to create in our society at all." This might be a little bit too close to the first question to be worth the time. "Not just to make pictures because anyone can do that. The real questions raised were in effect, where the painting and sculpture were in archaic form." Quote, "The original impulse of the New York school was that you had to prove to yourself that the act of creation was still possible." Did that strike a chord with you? Did that seem an accurate … or way to describe?

Jack Tworkov: Some of the question, I wonder whether it is possible to be creative today, really comes into it. In other words, there is a human impulse, a human instant involved, in painting, dancing, in expression of ... the other expressions, which goes back to the beginning of time. As long as mankind can exist, that's going to continue. Also, regardless of the world, we inherit an organic system, which is at work regardless of what the world ... And this is, after all, the basis from this day that creative act counts ... It's not whether you can be creative. It's the target, the focus that is vague and missing.

The artist, I don't think there's less creativity now than there ever was in the world. But the focus, the ability to achieve, the social organization to make it, is lacking. They're not less creative than the Egyptians, but they cannot make an art as great as the Egyptian art. Or the greatest art of any great period. We're just not in that kind of world.

Susan Manso: Because of the kind of vacuum …

Jack Tworkov: Yes, there's a kind of vacuum, where art, they're focused and concentrated on achieving something. Here it is dispersed in a million little directions. It lacks focus. It lacks the concentration of focus, but the creativity is there. People are not being born now less creative than they were in the past. It just determines so much what will happen to that creativity.

Susan Manso: Mm-hmm (affirmative), okay. This next comment, which was made by Robert Hughes the in The New York Review of Books. I think a pretty interesting article recently, I don't know if you read it.

Jack Tworkov: I think I read it. Yes, I think.

Susan Manso: Sublime. It's a lot about the marketplace, the money …

Jack Tworkov: Yes, I think I read that, yes.

Susan Manso: Which I think talks about in a serious way.

Jack Tworkov: Yes.

Susan Manso: Anyway, he said, "I wonder if it has any responsiveness." It's somewhat related to what we're talking about. "In the studio, Rothko was a man of resolution, one of the last artists in America to believe that his entire being, that painting could carry the load in an age of meaning, and possess the same comprehensive seriousness of the Russian novel." It's the kind of claim that I think is often made …

Jack Tworkov: I think that …

Susan Manso: ... about what the attitude towards his work, and he's not around to ask …

Jack Tworkov: Okay, I had enormous interest in Rothko and his work, and adore him as a person. But what is the point in comparing his work to a Russian novel? What now? Tolstoy? Dostoevsky?

Susan Manso: Well, it doesn't mean exactly the novel, but the notion. He's saying that Rothko believed that through and in his art, that he could, that he was making statements that were as big as, in 19th century …

Jack Tworkov: I think that that is something perhaps future history can foretell. Because, for instance, I doubt if anybody saw this, the social implications of impressionism when it came along. 100 years later, we can now see the social implications, even though nobody of the artists, or very few of the artists, really had a social point of view when they painted the impressionist paintings. We now see the emergence of that middle class culture in impressionism, that was from the Renaissance, that was from the religious thing, once and for all. They gave it up and they turned to nature, as you would expect 19th century people to do.

But they didn't rationalize it at all. You know? But it happened. Now, that Rothko's work has meaning, I'm positive. What meaning? I couldn't identify. I sense in Rothko's work a tragic element. An unexpressed tragic element, that lies deep in his work, in all of his work that I've ever seen. But, ask me to describe exactly what it is, I don't know. I don't know. I don't think that he was consciously aware of any kind of subject matter that he could have verbalized, that he could have put in words. I doubt it that much. That he believed in the meaning of his work, I'm absolutely convinced. Yes, he did.

Susan Manso: In some way, I think of course any painter would have to …

Jack Tworkov: Yes. The primary meaning of work today, the primary test of a work today, is it without pretense? Is it true, is there no pretense there? From that point of view, if the work is going to be an expression of self, if the work has no other focus. The only thing is, are you doing it out of an inner necessity? An inner propulsion? Does that determine the work? Or are you just waving to the art world for attention? And there's an awful lot of art that does. And Rothko's one of them. He was, "Hey," desirous of prestige and status in the art world. Nevertheless, you can see that nothing to that in his work. It was absolutely thought and experienced in the world.

And in fact, towards the end of his life, his great sadness was that he couldn't break out of it even. He wanted a change and he had found something so personal, so meaningful to him that he couldn't break out of that. He couldn't say anything. He used to constantly complain about that. Yet, if you asked him how did he feel, he says, "I'm bored, bored. He sits in the studio says I'm bored." It was an exaggeration, but that was his attitude. I once asked him, and he admitted it, he said, it had been such a struggle to find himself … an image, a direction that he could feel that it was his own, that he couldn't give it up. Because if he could give it up, he would be around right now.

I think that was a weakness. He could have done it, but he was also …

Susan Manso: It seems like a common trap, right?

Jack Tworkov: It's a very common … It's a very common trap.

Susan Manso: You said your ambition is to “paint no Tworkov’s.”

Jack Tworkov: That's right.

Susan Manso: That's a problem.

Jack Tworkov Yeah.

Susan Manso: I read something on [Bradley Walker] Tomlin just before he died that was beautiful about that. And there was something about also, he felt the need just at that point for some change because he felt he was getting a little too comfortable in …

Jack Tworkov: Yes.

Susan Manso: ... what he had found, but at such a cost anyway.

Jack Tworkov: I mean, after the struggle to find your subject, then inevitably you make some pictures, you start producing. But if you keep on producing, then you're losing contact with your trade of being. Production is not the aim of the artist in our time.

Susan Manso: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Jack Tworkov: It's not the condition for work in our time to keep on producing a mass of work. For me, the most beautiful example of the modern artist is Cézanne. To me, he is actually just, the purest of all the artists that I can think of.

L. B. #5 (CR 241), 1979, Graphite and colored pencil on paper, 22 1/2 x 30 1/2 in. (57.2 x 77.5 cm) Collection of the Estate of Jack Tworkov, New York

Susan Manso: We have somewhat hopeful and less heady questions. I'm going to quote something he once said about ... I can tell you where it came from, if necessary, but I haven't put it down here. You had talked about how, “for the painter, the consciousness, which is his in the studio is immediately modified when he steps outside. There he encounters the work of other painters, which reinforces all the tracks from his own. The galleries, which will or will not show his work, the museum curators that include or exclude him from important shows, critics that praise, condemn or ignore, informing the buyer and collector. Together they make up the art world, the market, and the politics of art. It would take enormous vanity to pretend that these forces do not affect a painter's development, since undeniably they affect his chances of survival. How can it be otherwise?"

I simply quoted this as a context for the next bunch of questions, some of which overlap. They're all trying to get at this whole business of art in relation to our society and how the art world market, politics, do affect the making of art.

First of all, I wanted to ask if you think it's possible for many artists to make their living solely on their art.

Jack Tworkov: Well, very obviously, some are making a living from their art, and some are even becoming very rich, as you know.

Susan Manso: Yes.

Jack Tworkov: But it's still not a great many. I mean, in terms of the vast number of artists, or people attending to art, the number that will make a living out of that is relatively very small, of course. Society … Just speaking of America, they pride themselves on culture, on being cultured and so forth. But it really and truly is based on a very, very small part of their life, of their daily life. Unless you have enormous wealth, you cannot afford to buy art, or very little of it. And so there's really no support for it, and as far as I can see.

In the greatest period, the support of the artist did not come from individuals, unless they were kings and nobles. The vast resources were already spoken for, were a culture for a given society, by the church. But, the day when we depend on the support of the artist for individuals in the marketplace. In other words, that's a very, very iffy thing. I doubt very much if ... Of course, I really don't know. I've never looked into it, but I imagine that the number of people actually living by their art is fairly small, fairly small.

Susan Manso: In the '40s, most artists ... I know there are exceptions. I don't think it's important who they are. My interest isn't to have a chart of who was really rich and linked to whatever. But in the '40s, most artists were very poor.

Jack Tworkov: Right. And did not expect to make any money out of that. Nearly every one, had some kind of trade or something that they pursued to support their painting: plumbers, carpenters, some advertising people.

Susan Manso: They said it's not as easy now because the unions make it impossible to be a carpenter. That the big place is teaching.

Jack Tworkov: Teaching. Well, at that time there wasn't that much teaching to be had. But that's the one thing that is better of art in the country … is their university art schools with jobs. But they were, is by no means an ideal situation for an artist to be on a university campus. I mean, especially on a permanent basis. I've seen more artists ruined by having tenured professorships at universities.

Susan Manso: You mean it makes them too safe or too academic? You think?

Jack Tworkov: Yes, I think so. Given our society, I think the artist still gets benefit from when he tries to make a living from his art, than if he tries to depend entirely on something else for his livelihood.

Susan Manso: Uh-huh (affirmative).

Jack Tworkov: The struggle to survive in the art world, even though, as I said, it involves some kind of compromise. It is very often a creative compromise. You know where the compromise lies …

Susan Manso: Uh-huh (affirmative). [crosstalk 00:27:38].

Jack Tworkov: And you persist as an artist. I think a great many people who went after a license to teach, simply lack the feedback, the incentive, or whatever it was. They just died on the university campuses. Many of them I know. I knew many of them. I could name a great many who left New York after the art projects were over. And they secured jobs in the middle West and the South and so forth. It was pitiful.

Susan Manso: I wasn't really into this, but I sometimes wonder what kind of painters it's going to produce, too. A lot of people had made cracks about it. Turns out ... I mean, they're paid but that's not ... It may mean that may also not be totally …

Jack Tworkov: Well, don't forget that there's an exaggeration about teaching art. Very few of the students are very much influenced by the faculty. If they're a good student, it tries to keep track of what is going on in art, and is much more guided by what he sees in magazines, what he sees in museums, and galleries, than the influence-able teachers. Because teaching art now is a fantasy. I don't think it exists.

Susan Manso: You've spoken about that, I think …

Jack Tworkov: Yes. And though I take occasional jobs like this, I have no illusions that I'm coming here to teach. I can sometimes, though, help a student understand his own situation. And in almost every art department you go to, their word is, that there are, sadly 5% of the students are actually brilliant… are really terrific. All over the country …

Susan Manso: It's a lot of …

Jack Tworkov: It's a lot of people and it's really a very curious question as to why this is happening to America. And not only in at but I’m told in poetry and music. On the campuses, I've heard some marvelous music, both performers and composers, young people.

Susan Manso: When we were talking about that, most artists having been quite poor. I think though in a serious sense, little has been made of that early poverty. Do you think that it was a factor in forming the attitudes, perhaps even the work, of many painters.

Jack Tworkov: I think so, because, the artist had given up on the possibility of making it in the art world. And career didn't lose a lot. Therefore, the concentration on what they were doing was very intense. You didn't have to live up to the gallery ideal. You weren't competing for attention.

Susan Manso: It says because there was nothing out there…

Jack Tworkov: There was nothing…

Jack Tworkov: You did, however, try to earn the respect of other artists. You see… You weren't just simply trying to make something that ... you know… the attention-getting thing …

Susan Manso: I can jump ahead. This is connected with a lot of questions. Is it any different now that, some painters say they paint for other painters? That that's finally one's audience?

Jack Tworkov: I don't think painters really give that much thought to the audience, whether it's other painters and so forth. What the artist is trying to do is ... is a … I think in our time, an artist becomes an artist because it is his way of achieving some kind of recognition of himself, some kind of identity of himself. I did say that someplace. The art that an artist makes, is a self-creation. He's creating himself, as well as making his work. That's his real test.

Susan Manso: The audience is irrelevant? Or get your own audience?

Jack Tworkov: It's certainly secondary. I mean, the sensation sometimes that you get from the studio, the pleasure, the achievements, et cetera is suddenly in ... You're there! as you weren't there before! A sense of being that you wouldn't have without it. The anxiety, which an artist experiences when he's separated from his studio for any length of time, is that he begins to lose this sense of being! to come back to the studio! To recapture a sense of being!

Susan Manso: Yes.

Jack Tworkov: I think this is in our time one of the major emotions, which an artist experiences. I don't say it was always that way, but I think, again, because of what I said earlier about our time, this is a major thing. An artist today tests the integrity of his own being, "Am I really there?" That is what art is about. And if he fails, if he thinks a picture comes out bad, he feels awful!

Susan Manso: They sense that you're the only one who knows me. It's very tricky about …

Jack Tworkov: In a sense, yeah, you're the only one who knows, but occasionally, some other person senses something in your work, and you can see by his reaction that he really sees it. Then it's a great pleasure too, because it's a verification. It's a verification. Every artist has experienced this occasionally. Somebody looking at his work really sees it, and it gives him that feeling of verification, so then "I'm not alone, I'm not crazy. I didn't just invent this. There is something to it. Somebody else sees this thing the way I see it." That's a ...

Susan Manso: I'm just nervous. I'm going to turn this over just ...

Jack Tworkov: I'm sorry that I made you …

Susan Manso: Oh, no, I'm just nervous we don't run out in a ... Now if I can figure out how to ...

SIDE TWO

Susan Manso: Let's see. What do you think of the WPA? What's the first time you were able to paint full-time?

Jack Tworkov: I would say that that's true.

Susan Manso: Because people often say that one of the big pluses about the WPA…

Jack Tworkov: Yes, for a few years, even though the amount of money was very little, they could live on it. And sometimes, they were amazed how well they lived on it. Because we made due on very little. This often, just that skimpiness was a pleasure. You had enough and you didn't have to worry about it. That part of it was very good.

Susan Manso: Was there pressure to paint political …

Jack Tworkov: Yes, there was.

Susan Manso: ... I know you said that you didn't like …

Jack Tworkov: Yes, there was.

Susan Manso: ... that you find your work of that period, at least?

Jack Tworkov: Yes, there was. There was a lot of pressure. Everybody would now know the artist union was really pretty much dominated by a communist traction. And there was a great deal of pressure, not only to paint, but the pressure to appear on picket lines, to be in demonstrations.

Some of the artists really felt sympathetic, to the cause, because, after all, the Hitler period, the Nazi period, a lot of artists were concerned as to what is happening to the world. They were sympathetic to ... And I remember a strike on the May Department Store. And we were asked to support the strike. We went there to be on the picket line with the May workers, and we were beaten up by the cops and so forth.

Well, it wasn't a problem. It was genuine sympathy. But it was organized very largely by communist action, in the union. I was also at that time fairly sympathetic to communism, until the trials came along, until the Nazi/Hitler party. I was still hoping that socialism was a true solution. I may still think so! I believe the disappointment is what happened in the Soviet Union and in other places. The disappointment was very great. I'm still not too happy with what they call [inaudible], and what is called democracy in our country.

But I certainly became disillusioned with the communists of that period. I wanted to stay away from ideology. For a long time, I couldn't bare any ideological ... The political ideological considerations.

As a matter of fact, I think the art of The Club, was largely composed by people who just simply rejected that whole business of the project, the need to get out of the communist, need to get out of this. So it had nothing to do with ideology. And the main ideologists never joined The Club, were never in the club.

Susan Manso: No. I won't put that, then.

Jack Tworkov: Yes.

Susan Manso: I know you've talked about dancing being a terrific aspect of the club. How about theory? How important at that time was it that painters got together and …

Susan Manso: The actual talking about art?

Jack Tworkov: It was very important, yes. I think so … talk be innovative but ... and sometimes it's very, very important. And at that time it was, and it was a very exciting period. And artists were finding new insights, and some conversation from each other. For a little while, it was really and truly very exciting, very stimulating, very exciting. Until The Club itself became a scene, with that everybody had to make that scene theirs.

Susan Manso: I guess, the impression that also ... I know you once said that it also became a career vehicle.

Jack Tworkov: Well, at least some artists thought this. Some of the younger artists that were brought into The Club as a way, looking, "It's a career for me." But it really started at first, quite innocent enough. It was really just truly a get-together for the artists, needing each others' support, needing each others' friendship. And it was very close for two years. It was very close.

Susan Manso: It does seem in general that, in some ways, it was a more innocent time.

Jack Tworkov: Yes.

Susan Manso: But what Allan Kaprow said in the mid '60s, once said that, a snappy, [inaudible 00:39:58] that artists were in hell in 1946, then by 1965, they were in business.

Jack Tworkov: That's firmly true.

Susan Manso: You think they, in a way, there's something to that?

Jack Tworkov: Yeah, there's something to it, because by 1965, the possibility for many of the artists that making it, I think was already there. And once you started making it, from art, then you want to do it faster, and you want to do. I think was de Kooning that said, he used to say they are [inaudible 00:40:35]. Ironically, but I think he meant it. He meant it.

Susan Manso: It says, maybe they're just not talkable about that but it does have consequences for art and artists, does it not? And that there's a very big difference between the world now and in the '40s. Very little is ever said about ... being … I don't know how we could about what the consequences of the change, in art being ... for some painters. I realize the majority work very hard and are not in big business, but somehow it has a very difficult …

Jack Tworkov: I think, for the most artists that ever made it in the art world, they really didn't start out that way. I don't think that's really what had happened to them. And often, psychologically, [inaudible 00:41:14] I think it was the Rothko. Because Rothko only became ... He started making money only in the last 10 years of his life. Up to that time, he hardly made any money from his work. And I think he had a hell of a time absorbing the situation, since he also was very bad in the use of money. He had no idea what to do with money.

Susan Manso: I was going to ask you about a statement, again, by Robert Hughes, who had said, "What the terminal act was the climax of a long troubled separation for a failure that eluded him." And what he was talking about there was, in fact, Rothko's difficulty, he said, in dealing not so much with success but with money, with having made it.

Susan Manso: And people have said, Dore Ashton said all over the place that was true of a lot of painters at that time.

Jack Tworkov: I know a lot of people when they started making an awful lot of money went into a shock, psychological shock. I hate to mention it, some of the people ... But I knew one who had very, very great success. And for several years, couldn't work, couldn't really tend to his work. All he was trying to do was to escape from [inaudible 00:42:55] artists just didn't know how to deal with it.

Susan Manso: Uh-huh (affirmative). But this brings up, there's an attitude often and lots of writers talk about that. There's an attitude that society killed abstract expression is that they were, in [Antonin] Artaud's phrase, "suicided by society." How do you feel about that?

Jack Tworkov: I think that's correct.

Susan Manso: So that approach to Rothko and Pollock?

Jack Tworkov: I really think that's correct … Of course, part of the problem is that, very difficult for an artist to find ego satisfaction. You must work alone. Very often, he starts looking towards the world for ego satisfaction. Rothko was a perfect example of it. He hated the art world. Hated all the people connected to it. He wouldn't come to dinner, unless you were certain there were artists and real people and museum curators and critics or something like that.

Jack Tworkov: At the same time, he was zealous for them to say Rothko is the greatest. He wanted them to ... and that's some kind of a madness, I think. I think a lot of artists had that.

Susan Manso: Does it get in the way of the work? I mean, a lot of people have said because of the change by, Larry Rivers once said in the '40s he had to work, and he had few friends, and one saw one another's work, but that was it. But now, about half of one is out. You're half in the studio and half [inaudible 00:44:49]. I think he set it up himself. And are half looking toward the world.

Jack Tworkov: Well, I'm sure that's true of some artists. I also think that some artists have tried to maintain a certain kind of privacy for themselves … content to get along but I'm not really struggling!

Susan Manso: I was going to say, and maybe this is my own romanticism, possibly, though, at the expense of making it later, I mean? I guess what I'm asking is, if you pay a bit of attention to that part out there, is it likely you get further in terms of money, recognition?

Jack Tworkov: I think that if you have skill in that area, you might do very well for yourself. On the whole, I think that the people who have made it genuinely, in one-way or another, considering the system. But I think there's, here or there, I think some people prosper from relationships, significant relationships in the art world. Authored it, promoted it.

Susan Manso: I would like to think in the long haul that work would …

Jack Tworkov: Sometimes it dependent a lot on how big a salon you have! Yes. If [inaudible 00:46:35] you could give really clever parties in that [inaudible 00:46:38].

Susan Manso: It becomes a big circle because through that you then got a good gallery, which in turn meant you sold more, so you have more time to work, and so forth. It could become very ... I wanted to ask you how important these galleries were? Gallery owners in your development, at all? Especially Charles Egan because he promised [crosstalk 00:47:04].

Jack Tworkov: I think that my relationship with galleries has always been a very good one. And I've always been amazed at how cooperative they were and how helpful they've been to an artist. I never had any complaints about the galleries. I've never felt exploited. But then I've also been associated with very few galleries, and I think they're very good galleries. I was with [Charles] Egan, the Stable Gallery, [Leo] Castelli, and now this gallery here.

Susan Manso: You mean Nancy Hoffman?

Jack Tworkov:

Nancy Hoffman. And my experience has been that they've always been supportive, they've always been helpful, they've always been an anchor.

Susan Manso: Is Charles Egan incidentally, as a side part, alive?

Jack Tworkov: I think so. I really don't know. At last count I …

Susan Manso: I wanted to try to get ahold of him because, one chapter I wanted to [crosstalk 00:47:53].

Jack Tworkov: I haven't heard that he isn't. I hadn't kept in touch with him for a long time. I think that there's a tendency sometimes to say foolish things about galleries. But my experience on the whole has been that galleries are very supportive of the artist.

Susan Manso: You have the same experience at museums? Of course, they're not comparable [crosstalk 00:48:13].

Jack Tworkov: Well, the museum situation is somewhat different, I think, because, the museum curator is as out to use art for his career and his ego, in a way which I don't think that …

Susan Manso: Gallery?

Jack Tworkov: Gallery. If the gallery wanted to make money, it is not harmful to the artist. It helps the artist.

Susan Manso: Correct.

Jack Tworkov: But very few galleries are trying to supplant the artist as [inaudible 00:48:57]. But the museum people, a lot of them, as museum people, is focused on their own career, what will make their career.

L. B. #8 (CR 578), 1979, Pastel, pen, ink, and graphite on paper, 22 7/8 z 30 3/4 in. Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchased with funds from Mr. and Mrs. William A. Marsteller (83.7)

Susan Manso: I believe you didn't ... I'm switching a little bit, but did not paint between somewhere in 1942 and 1945?

Jack Tworkov: Yes, I worked for a while as a tool designer as an engineering after the war.

Susan Manso: So the reason for not painting, is you had to make a living?

Jack Tworkov: Well, that, but also I think, art at that time was very much concerned with the war. Even the ones who …

Susan Manso: I wanted to ask you about that because it's funny …

Jack Tworkov: Even if they weren't soldiers, those who were soldiers, some of them, they didn't believe in fighting, that Germany would attack. And others felt, well, if they can't be soldiers they would love to work in some war effort. At least at the beginning it was so. After a while, it became a little bit cynical, but I remember quite definitely, I felt pretty good about the idea that I was going to contribute something to the ...

Susan Manso: Uh-huh (affirmative). That's because, I read somewhere Rosenberg had said that, "If the war and the decline of radicalism were relevant, there is no evidence about the effects of large issues on their emotions. Americans seem to be either reticent or unconscious." And I thought, that seemed to me a strange thing to say. And I come across …

Jack Tworkov: I think that a …

Susan Manso: ... responses much more like yours.

Jack Tworkov: I think that at that time, people were really resented… Nobody at that time could have imagined losing the war to the Nazis. It everyone … could have thought that it was a terrible threat, and so everyone wanted to help.

Susan Manso: It is interesting to me, that in all of the usual discussions of the genesis of abstract expression, as in the history of it, that it's always a ... take some surreal that doesn't take some ... a lot of it's negative response to the social mores, this and that of the '30s and the Depression. But usually the war is not talked about.

Jack Tworkov: No.

Susan Manso: Mainly because ... I don't know why but the war is not discussed as a course.

Jack Tworkov: [crosstalk 00:51:37] discussed was the frightful disappointment that came about after the war, about this illusion that came after the war. I remember distinctively that when the war ended, I naively had such optimism. I really thought that we were now taking a turn for the better. No one imagined that it would ... the kind of hell that was going to come after that! The second world war and all. Even the cooperation of the United States with the Soviet Union seemed like an interesting possibility.

Jack Tworkov: But then the Cold War developed, and the nuclear armament began. The nuclear threat began, and so forth. So that the optimism that came with the end of the war was extinguished and then people, again, had nothing to say.

Susan Manso: And beginning now the disillusion that [crosstalk 00:52:39]

Jack Tworkov: That's it, another ... Yes, yes.

Susan Manso: ... public or political.

Jack Tworkov: Yes. Listen, dear, I have to go, but I'll tell you, if you ever [inaudible 00:52:47], I would be glad to meet with you again, if you'd like.

Susan Manso: Oh, that's very kind of you.

Jack Tworkov: Yes. But I really have to stop now because these people are waiting for me.

END

__________

Susan Manso was a writer. In 1977 she co-edited along with Partricia E. Kaplan “Major European Art, 1900-1945,” published by E.P. Dutton, New York.