TWRKV: Rauschenberg's Greatest Champion & Friend

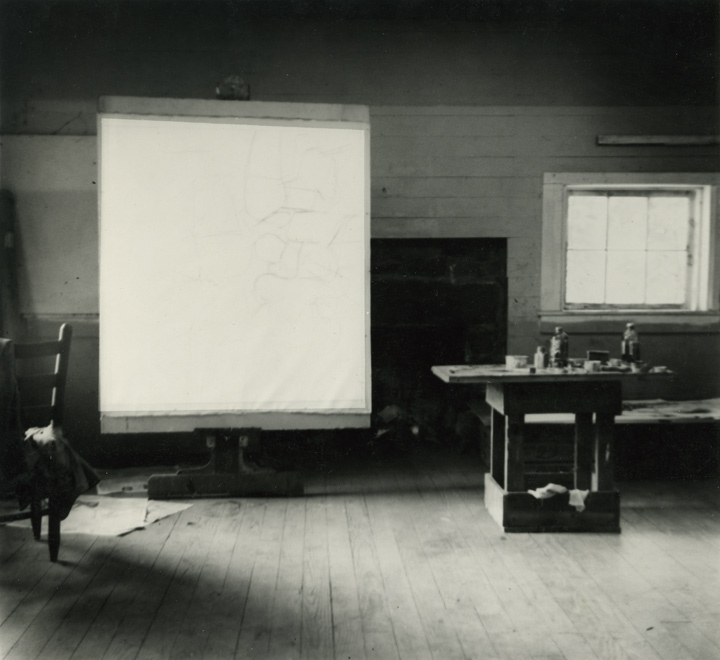

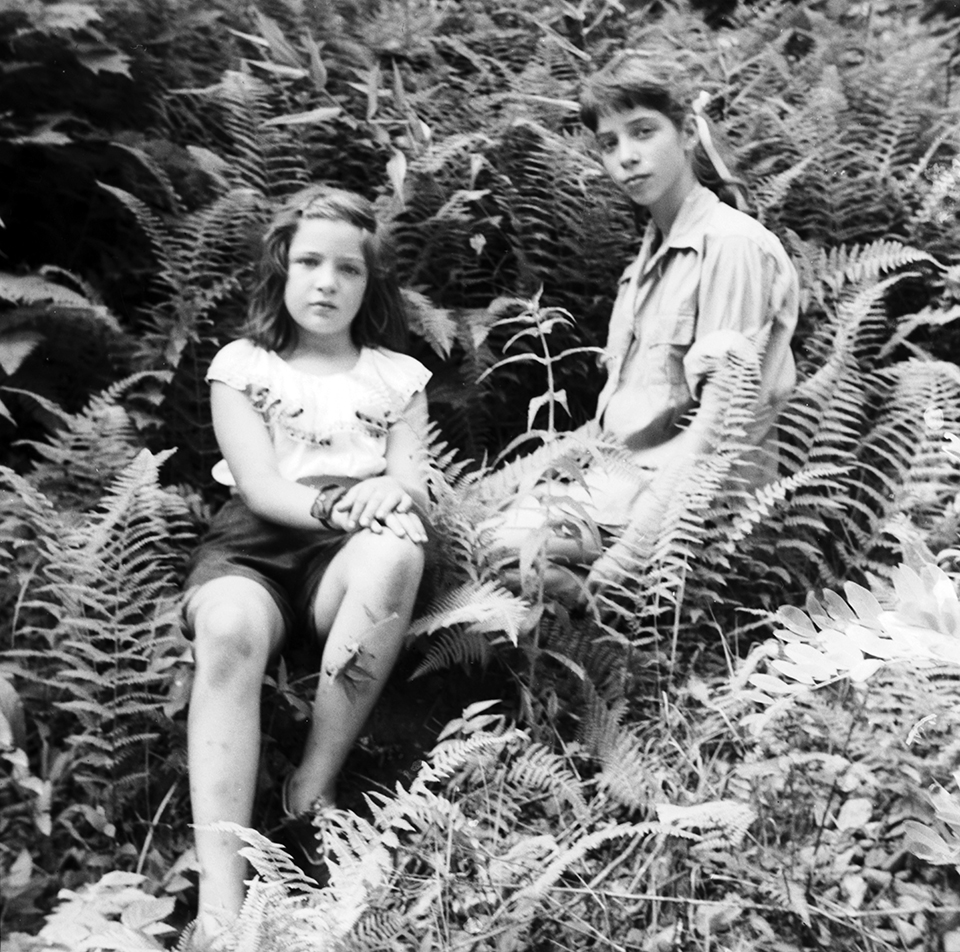

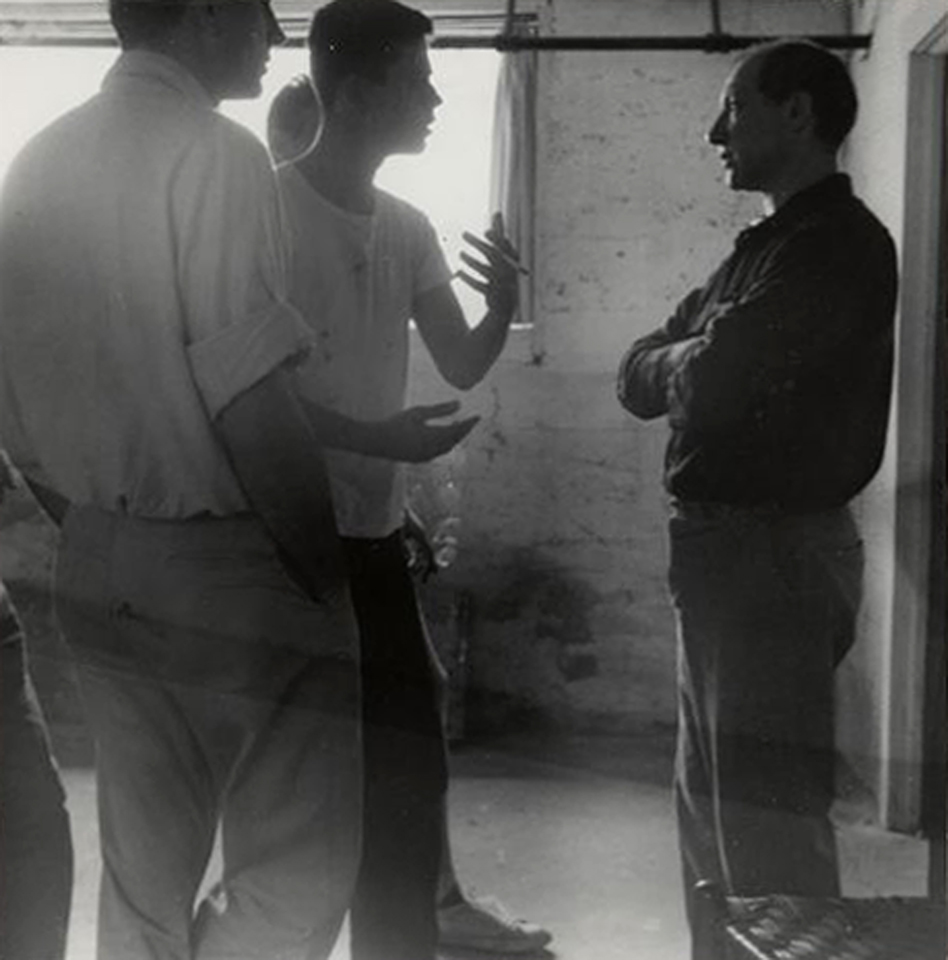

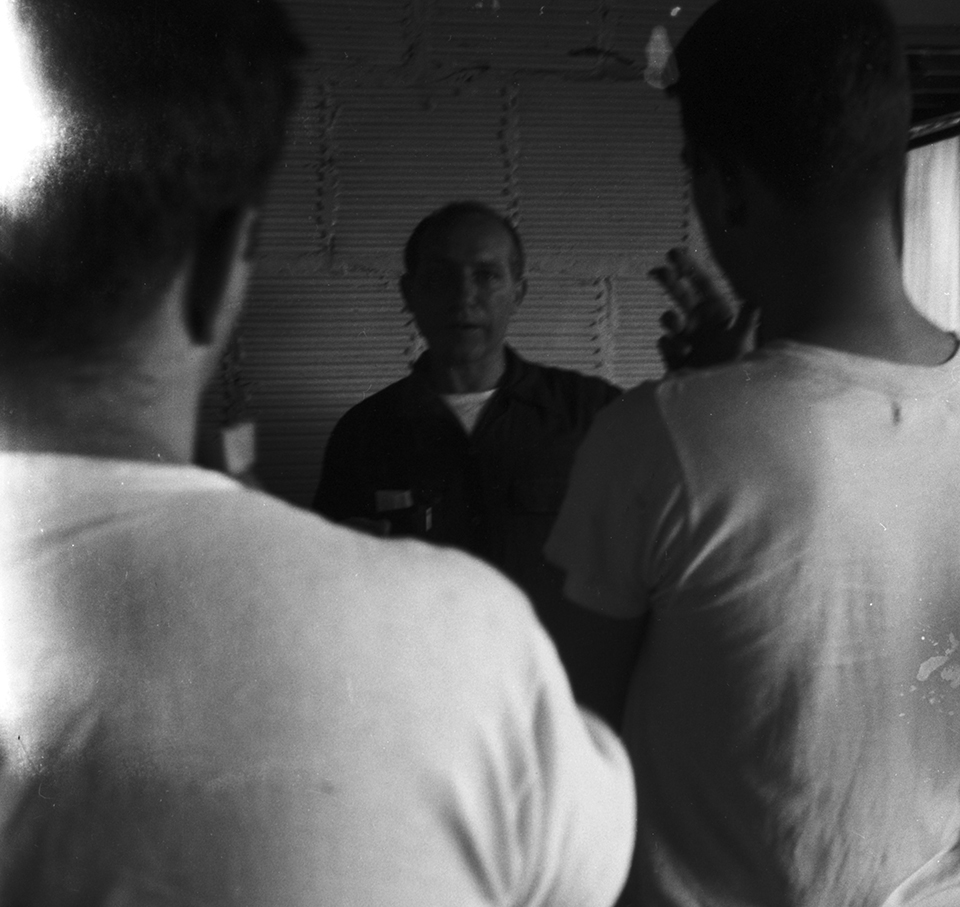

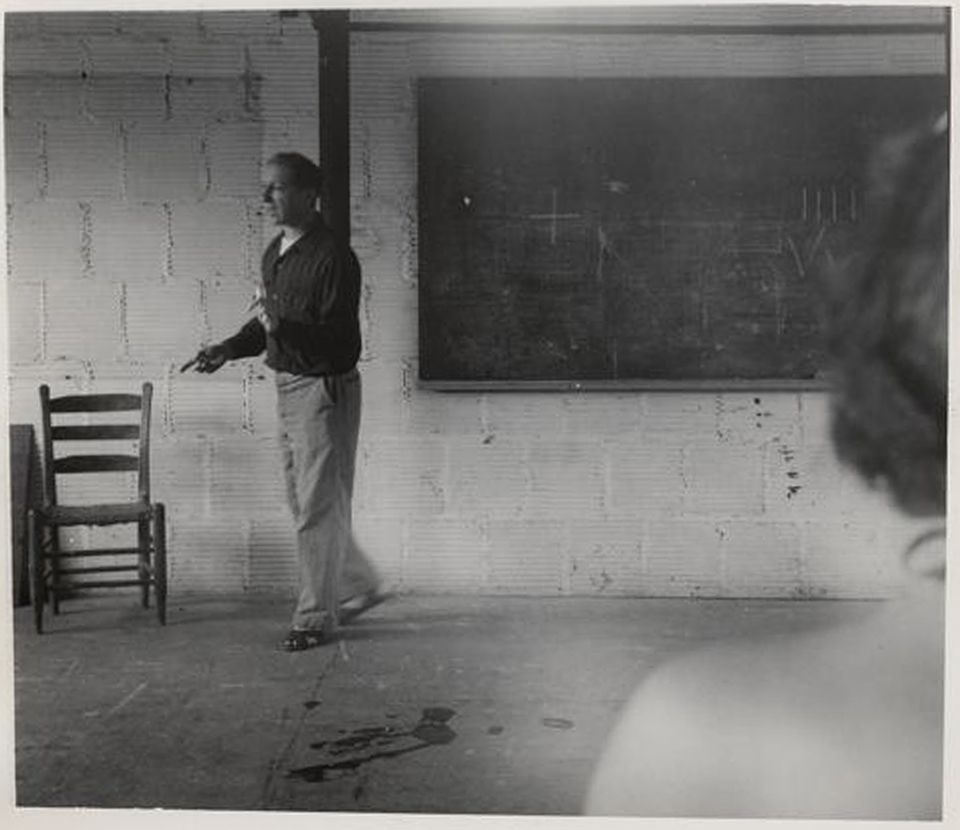

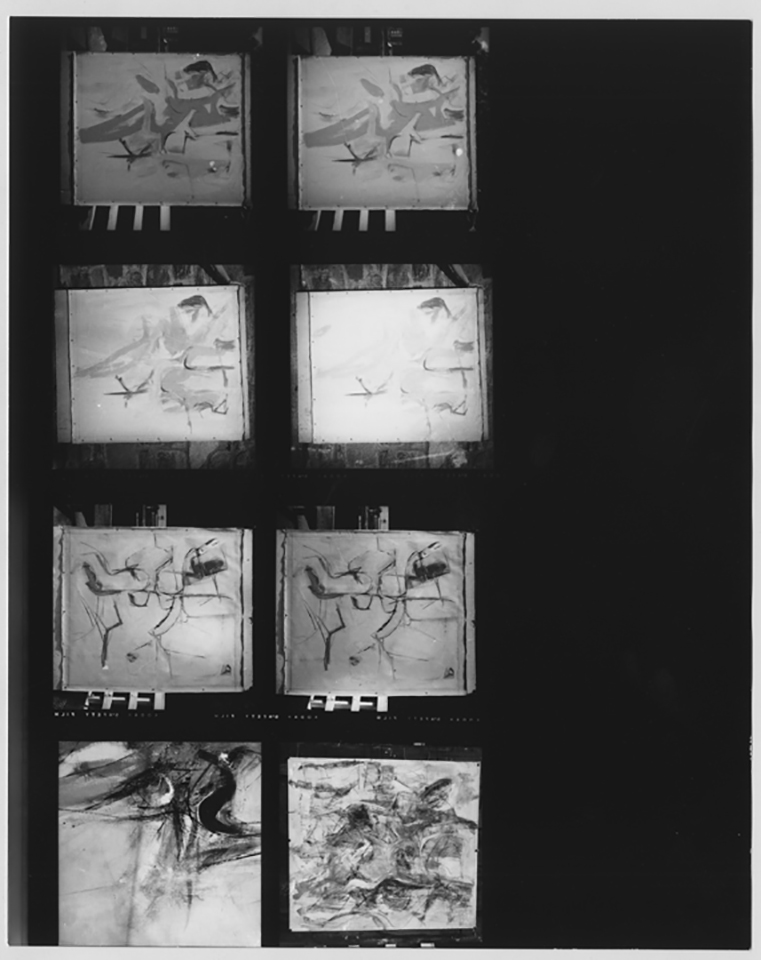

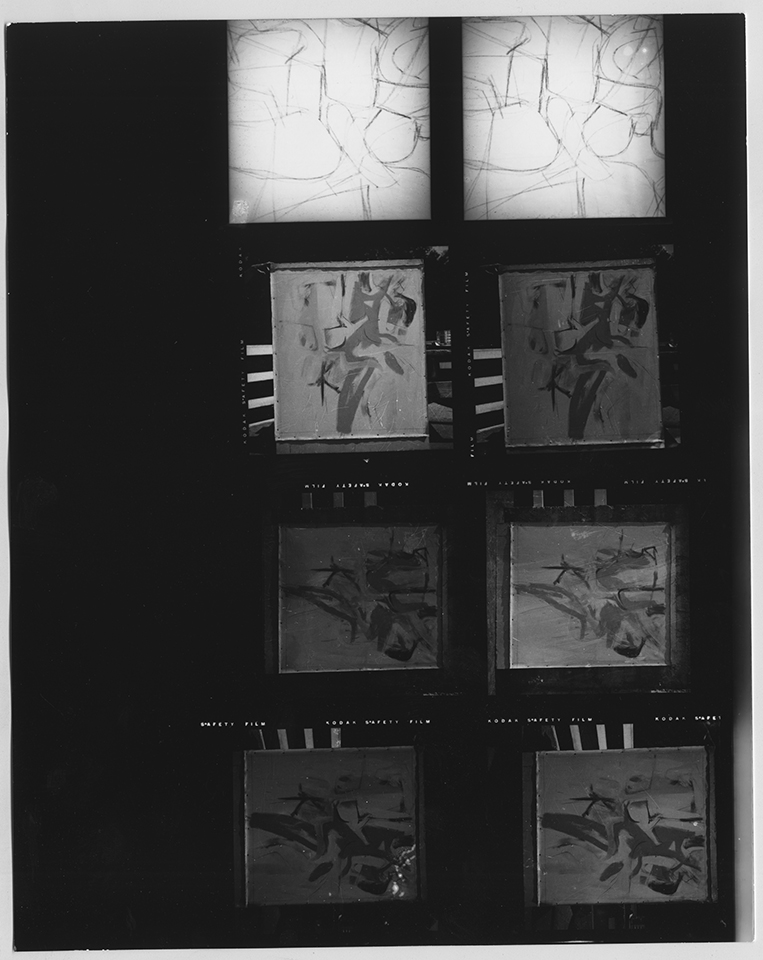

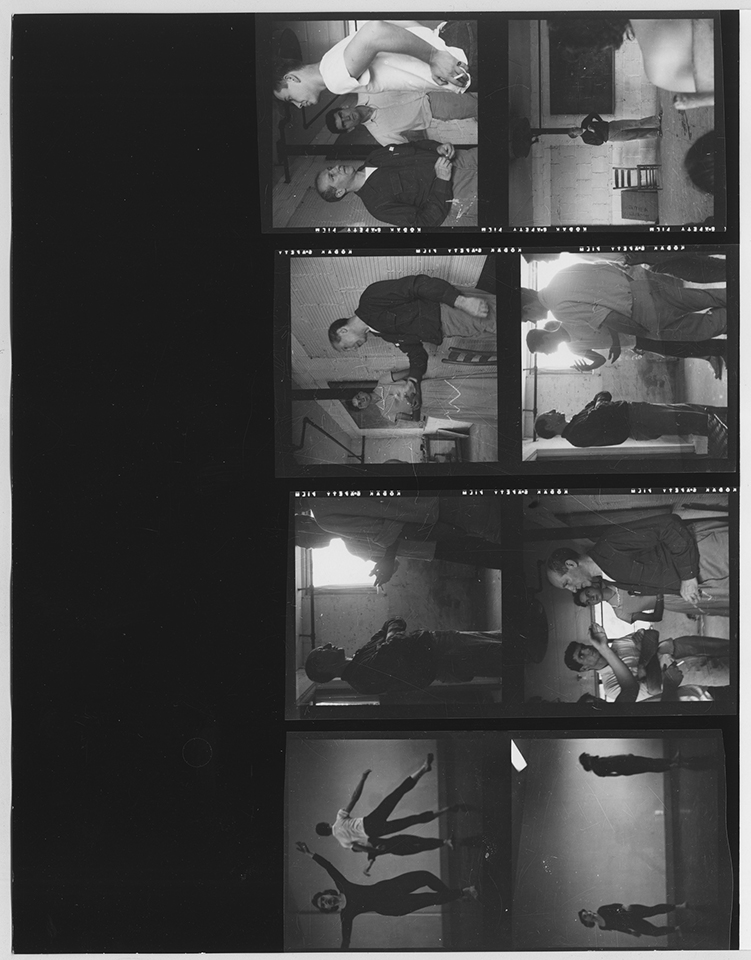

Jack Tworkov at Black Mountain College, 1952. Photos by Robert Rauschenberg © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Rauschenberg's Greatest Champion & Friend

by Jason Andrew

Note: The following essay was originally published in "Jack Tworkov: Accident of Choice, The Artist at Black Mountain College 1952," which coincided with an exhibition of the same title held at Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, Asheville, NC, June 17-September 17, 2011. It has been modified from the original.

Robert Rauschenberg had relatively few admirers among the older generation of Abstract Expressionists. Many labeled his antics as "anti-art," while others disregarded him all together. Rauschenberg marked a new wave of artists, that included Jasper Johns, coming up through the ranks that threatened to de-thrown the older generation, which by the mid-late 50s was finally experiencing success and solid sales. Yet among the patriarchal New York School, the young Rauschenberg found one of his greatest and earliest champions in Jack Tworkov.

Although differing in temperaments, Tworkov and Rauschenberg did have one thing in common. They both shared a common adversary: hundreds of years of European history, theory, and dominance in the arts. And while Tworkov and the other Abstract Expressionists, having themselves rejected the classical canons of composition, it was Rauschenberg who would take the art world to the next level.

Tworkov and Rauschenberg were likely introduced through their mutual friends the choreographer Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage, but the pair really came to know each other the summer of 1952 at Black Mountain College.[1]

In his book Off the Wall: A Portrait of Robert Rauschenberg, Tworkov told Calvin Tompkins that he was drawn to Rauschenberg immediately because of what he described as Rauschenberg’s “sense of comedy, his high comic spirit,” and his attitude of “you never know how it’s going to look until you do it, so let’s do it.”[2] Tworkov “liked the energy and the directness of his approach.”[3]

“Bob has always been able to see beyond what others have decided should be the limits of art,” Tworkov told Calvin Tomkins, and goes on to place Rauschenberg in context for his time:

Twentieth-century art has been a constant expansion of these limits, of course—people once thought that Cézanne had gone as far as you could go. But Bob always wants to go still further. Look at what he did with collage. If it was all right to make pictures with bits of pasted paper or metal or wood, he asked, then why couldn’t you use a bed, or even a goat with a tire? He keeps asking the questions—and it’s a terrific question philosophically, whether or not the results are great art—and his asking it has influenced a whole generation of artists.[4]

A point rarely discussed, yet possibly critical to Rauschenberg’s unique attraction to Tworkov, may have been that Tworkov was a family man. Rauschenberg had recently become a father himself (his son Christopher was born in the Summer of 1951). Tworkov, unlike many of the other larger-than-life figures of the New York School like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, or Franz Kline, was an attentive husband and caring father. These were traits that “did not hold a lot of credence with the students at the time,” explains Black Mountain historian Mary Emma Harris. “Kline was the star of the summer [1952]. He hung out with the students, went to the local beer joint, and drank with them at the Cedar Bar in New York. Tworkov was a family man.”[5]

In the Summer of 1952, Rauschenberg had become increasingly more interested in photography, in fact, that summer, he became “obsessed at Black Mountain with the idea of photographing the entire United States, virtually foot by foot, an idea so ambitious that it would probably have taken him, as he later calculated, about ten years just to get from Black Mountain to Asheville.”[6]

Twentieth-century art has been a constant expansion of these limits, of course—people once thought that Cézanne had gone as far as you could go. But Bob always wants to go still further. Look at what he did with collage. If it was all right to make pictures with bits of pasted paper or metal or wood, he asked, then why couldn’t you use a bed, or even a goat with a tire? He keeps asking the questions—and it’s a terrific question philosophically, whether or not the results are great art—and his asking it has influenced a whole generation of artists.[4]

A point rarely discussed, yet possibly critical to Rauschenberg’s unique attraction to Tworkov, may have been that Tworkov was a family man. Rauschenberg had recently become a father himself (his son Christopher was born in the Summer of 1951). Tworkov, unlike many of the other larger-than-life figures of the New York School like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, or Franz Kline, was an attentive husband and caring father. These were traits that “did not hold a lot of credence with the students at the time,” explains Black Mountain historian Mary Emma Harris. “Kline was the star of the summer [1952]. He hung out with the students, went to the local beer joint, and drank with them at the Cedar Bar in New York. Tworkov was a family man.”[5]

In the Summer of 1952, Rauschenberg had become increasingly more interested in photography, in fact, that summer, he became “obsessed at Black Mountain with the idea of photographing the entire United States, virtually foot by foot, an idea so ambitious that it would probably have taken him, as he later calculated, about ten years just to get from Black Mountain to Asheville.”[6]

During Tworkov’s stay, Rauschenberg documented Tworkov in the studio, in the classroom, and photographed Tworkov’s two daughters, Hermine and Helen, in the fields and hills that made up Black Mountain. These photographs illustrate a unique love and affinity Rauschenberg had for Tworkov and his family. “Rauschenberg and my father were very fond of each other,” recalls Hermine Ford. “Rauschenberg’s presence was very felt. We all loved each other!”[7] Tworkov believed in Rauschenberg “so much so that Tworkov undertook to store a number of the white and black paintings in his New York studio when the summer was over.”[8] It was Rauschenberg who assumed the responsibility of packing up Tworkov's studio that summer and arranging for the works to be returned to New York.

Jack Tworkov, Robert Rauschenberg, Black Mountain College, 1952

Jack Tworkov, Robert Rauschenberg, Black Mountain College, 1952

Aside from the familial attraction, Rauschenberg undoubtedly was drawn to Tworkov’s artistic philosophy. Tworkov “encouraged his students to explore other means of expression,”[9] and to “see beyond what others have decided should be the limits of art.”[10] Rauschenberg found encouragement in these statements—sympathy towards his experimental nature. Tworkov wrote in 1948, “if advanced painting is not unexpected then how is it advanced?”[11]

In an unpublished essay, written sometime in the early 1960s, Tworkov explains the significance of Rauschenberg’s work:

It’s difficult for anyone experienced or inexperienced in art to accept Rauschenberg’s object of a shaggy goat with a rubber tire around its middle, its nose desecrated by blobs of paint as a sculpture or a painting or as an art object. The inevitable meaning of these objects is in the shock of the sensibilities, it attacks the commonplace by substituting commonplace objects for art […] More to my point is the presentation by Rauschenberg of completely unpainted panels in his first exhibition at the Stable. Just as an audience was booming for Mondrian, Rauschenberg’s totally empty canvases asked, how far can you go? If you are interested in beauty, what’s wrong with a totally empty canvas? (This is all the more interesting in the light of the fact that when Rauschenberg turns to “legitimate” composition, he is one of the most talented and brilliant painters of the abstract movement.) [12]

The elder artist did a great deal to promote his young friend. As Calvin Tompkins records, "Tworkov kept encouraging [Eleanor] Ward [Stable Gallery] to go down Rauschenberg’s studio, and early that summer she did go to Fulton Street, where she saw the white and black pictures and several of Twombly’s abstractions. She offered them a joint show in the fall."[14]

Tworkov continued to give Rauschenberg “full, active, and generous support.”[15] It was at Tworkov’s insistence that Rauschenberg was later accepted into the Charles Egan Gallery in 1954.

“Tworkov showed with Charles Egan, whose gallery, at 46 East Fifty-seventh Street, also represented de Kooning, Kline, Guston… Egan had not taken on a new artist for a long time, but Tworkov kept after him, and finally Egan consented to come down with Tworkov to the Fulton Street studio. Rauschenberg was not overly hopeful about the visit, nor did Egan seem particularly enthusiastic about the gaudy new red paintings. After he had been there for a while, though, he asked Rauschenberg how soon he could be ready for a show. ‘About a week,’ said the artist, Egan gave him a month.”[16]

A letter to Jack Tworkov in New York from Robert Rauschenberg, which was dated from Black Mountain College, early August 1952, offers insight into the relationship built that summer:

Dear Jack-

I miss you and yours very much! I apologize for not getting the package off sooner. It was the day after Franz [Kline] wrote you. The photos of the paintings and a couple of you in lecture went off this afternoon you should get them in a couple of days […] I’m anxious to print the negatives of Helen and Hermine. Tell Wally I sent the other package to the studio too because it saved about $2.00 […] My dear Jack you and your family gave everyone at B.M.C. something to think about. Even Tommie [the dog] has not gone back home. I will write again, but not so hurriedly next time.

Love, Bob[17]

Rauschenberg at his Fulton Street Studio, 1953. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

A letter to Tworkov from Rauschenberg, dated Rome, early September 1952 is equally affectionate:

Dear Jack

Dear Wally

Dear Hermine

Dear Helen

The trip was fine—abit [sic] long, but over. We stoped [sic] in Palermo[18] and hated it. Everyone was out to get us and I was offended by the Sicilians folksyness [sic] and complete abuse of anything classic or BIGGER. We got a boat train and headed right for Rome. We are settled in Marci-Relli’s [sic] very room. We made her come down a little on the price. We eat in local resturants [sic] for very little, but everything here is just as expensive as the states. So don’t you believe it. We have to watch every penny. Rome is really a beautiful place I’ll write more about that next time. The next letter will come from the Vatican. Because air mail is less. The American Express is the address to use it is just across the Piazza. By the way did I leave my home made shirt at your house? If so just keep it for me if you don’t mind. This note is really not to tell you about me, but to thank you for N. Y.

Love Bob

Cy wants to say hello.

BOB

P.S. Your letter seemed distracted. I do hope you are not put-out by me. I will make amends if you are, dear Wally.[19]

A hurried letter to Wally Tworkov from Robert Rauschenberg, dated Rome, Monday, Oct 5 1952, demonstrates that the young artist’s friendship was not limited to Jack:

DEAR WALLY.

I got your letter this morn. and have made a rule about ans.ing [sic] on same day because I’m actually a great procrastinator (at least I used to be). I’m really glad you met Topher.[20] I miss him more everyday. I dreamed all night last night about buying him clothes and loosing him in a dept. store and when I found him some Italian had him as his own and I couldn’t convince anyone that he was mine because I didn’t speak enough Italian. It was hell I’ll be glad when my dreams are in either completely [sic] Italian or English. I don’t even know what[s] going on half the time in them now. I am going to Casablance [sic] tomorrow by way of Tunnis [sic] to see if I can get a job and work there for about 6 mo. So I’ll have enough money to go to Egypt and Greece. I hear Casa isn’t much, but I’ll take short trips into the desert and Marakish [sic] is reported to be a completely different world. I know am crazy for Rome, but there is absolutly [sic] nothing in painting going on. I will find it hard to leave my beautiful B.C. Etruscans. I just got back from Florence. Cy and I went up, & scratched Michel Angello [sic] and that silly sissy Fra Angellico [sic] off the list and I’m sick to my stomach of Martyres [sic], Saints and Christ. Giotto far surpassed my already extreme compassion. We went to Assisi, Perguia, and Siena. In Siena there are terrific Duccio’s but that’s about all. I’ll probably be impossible when I get back to New York with all my first hand references to back up or rationalize by already formed esthetics. Was Helen seriously ill? I hope not. I will write to Carol about photos. Did Sue tell you about the house burning down—luckily, no one was hurt. Tell Jack to write me about the painting and showing New York. You can put in the shades of the situations. I really am lonesome for MY PAINTING LIFE so if I know something about what’s going on it gives me away to think of it. MY LOVE TO YOU ALL. Please continue writing Rome. I don’t know my next address. It will be forwarded.

BOB[21]

The friendship between Tworkov and Rauschenberg would never fade. Rauschenberg valued Tworkov's insights inviting him regularly to visit his studio throughout the early 60s when they both exhibited at Leo Castelli Gallery. On one such occasion Tworkov wrote in his journal, "I visited Bob Rauschenberg's studio this morning and enjoyed my visit. I must write more about his in my note." [22] Although time would but distance between them, it never effected the love and compassion they felt for each other.

Tworkov, interview by Mary Emma Harris.

Calvin Tomkins. Off the Wall: A Portrait of Robert Rauschenberg (New York: Picador, 2005) 67.

Tomkins, Off the Wall, 73.

Calvin Tomkins. The Bride and the Bachelors (New York: Penguin Group, 1965) 193.

Mary Emma Harris, letter to the author, May 23, 2011.

Tomkins. Off the Wall, 80.

Hermine Ford, interview.

Tomkins. Off the Wall, 67.

Delia Gaze, ed. Dictionary of Women Artists, (Chicago, Illinois: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997) Vol. 1, 218.

Michael Kimmelman. “Robert Rauschenberg, American Artist, Dies at 82,” The New York Times, May 14, 2008.

Jack Tworkov. Artist’s Statement, Baltimore Museum of Art News 12 (November 1948), 4.

Schor, Extreme, 193.

Tomkins. Off the Wall, 97.

Tomkins. Off the Wall, 85.

Tomkins, Bride, 212.

Tomkins. Off the Wall, 107.

Robert Rauschenberg, to Jack Tworkov, circa early August, 1952. Jack Tworkov papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Leeman, Richard. Cy Twombly: A Monograph. (Paris: Editions Flammarion, 2005): “Around 20 August, Twombly boarded a ship in New York with Rauschenberg and after stop over in Palmero and Naples arrived in Rome in early September. Rauschenberg then went off to Morocco where Twombly joined him at the end of October. They went back to Rome in February.”

Robert Rauschenberg, to Jack Tworkov, September, 1952. Jack Tworkov papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

According to David White, Curator of Robert Rauschenberg Studio, this is likely a reference to Rauschenberg’s son, Christopher, born July 16, 1951. David White, email to the author, May 23, 2011.

Robert Rauschenberg, to Wally Tworkov, Monday, Oct 5 [1952]. Jack Tworkov papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Journal Entry, Saturday, December 1, 1962.